The tomato arrives in January. It sits on the plate like a confession nobody asked for — pale, mealy, shipped from a Mexican hothouse eighteen hundred miles south, yet the chalkboard above the bar reads “Local Heirloom Tomato Salad.” The diner pays forty-two dollars. The farmer whose name appears on the menu hasn’t sold to this restaurant in eleven months. And somewhere on the North Fork, a man who has spent thirty years coaxing flavor from Suffolk County loam watches his reputation get borrowed like a library book that nobody intends to return.

This is the state of “farm-to-table” dining on Long Island in 2026 — a phrase so thoroughly co-opted that even Dan Barber, the chef whose Blue Hill at Stone Barns became the cathedral of the movement, has publicly disowned the term. In a 2024 interview marking Stone Barns’ twentieth anniversary, Barber admitted the expression has become little more than a marketing veneer, an opaque shorthand that obscures more than it reveals (Resy, 2024). The man who arguably did more than any living American chef to forge direct connections between field and plate now considers the phrase a failure.

After twenty-five years behind the counter of The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai — a quarter-century spent negotiating with the same produce distributors, the same Sysco representatives, the same local growers who still answer their phones at five in the morning — I have earned the right to say what most restaurateurs will not: the majority of “farm-to-table” claims on Long Island are, at best, aspirational poetry and, at worst, consumer fraud. The chalkboard is lying to you. But the land itself never does.

The $373 Million Dollar Question: Long Island’s Agricultural Paradox

Here is the central irony of our island’s food economy: Long Island possesses one of the most productive and expanding agricultural sectors in the entire state of New York, yet the vast majority of restaurants operating within arm’s reach of those farms serve commodity ingredients sourced from industrial supply chains.

According to a November 2024 report from New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli analyzing the USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture, Long Island was the only region in the state to see growth in both the number of farms and total farmland acreage over the preceding five years. Suffolk County added eighteen farms while the state as a whole lost over eight percent of its agricultural operations during the same period. There are now 607 farms cultivating 34,468 acres across Long Island, generating nearly $373 million in total agricultural sales — a staggering sixty-four percent increase from 2017 (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2024).

More telling still: Suffolk County leads the entire state of New York in direct-to-consumer agricultural sales, with over $268 million flowing directly from farm to table — the real table, the one at the farm stand or the CSA pickup, not the one with the forty-two dollar tomato salad. The infrastructure for authentic local sourcing does not merely exist on Long Island. It thrives. The question is why so few restaurants bother to use it.

The answer, as it always does, comes down to margins. Running The Heritage Diner for twenty-five years has taught me that the economics of genuine local sourcing are punishing. A case of commodity tomatoes from a national distributor might cost a restaurant thirty dollars. The same volume of heirloom varietals from a North Fork grower costs three to four times that, arrives in smaller quantities, demands refrigeration within hours of harvest, and disappears from availability the moment the season turns. The restaurant that commits to real local sourcing doesn’t just change its supplier — it changes its entire operational philosophy. The menu must bend to the calendar. The walk-in cooler becomes a living document. And the profit margin on every plate shrinks by a percentage that would make most investors reach for the Sysco catalog.

This is why the phrase persists as marketing rather than practice. It is easier to write “locally sourced” on a chalkboard than to restructure a kitchen around the tyranny of seasons.

The Anatomy of a Farm-to-Fable: How Restaurants Fabricate Provenance

The investigative template for farm-to-table fraud was established in 2016, when Tampa Bay Times food critic Laura Reiley published a devastating multipart exposé documenting systemic deception across Tampa’s restaurant scene. Reiley carried zip-top bags in her purse, collected fish samples, and had them DNA-tested at the University of South Florida. She visited the farms whose names appeared on menus. She called producers and vendors. Her conclusion was unequivocal: virtually everyone was telling tales, ranging from outright fabrications to negligent omissions to what she termed “greenwashing” (Tampa Bay Times, 2016). A parallel investigation by San Diego Magazine uncovered identical patterns on the West Coast, coining the phrase “farm-to-fable” that has since entered the culinary lexicon (San Diego Magazine, 2016).

The patterns Reiley identified are not exotic. They are banal, repeatable, and operating in plain sight across Long Island’s dining landscape. They include restaurants that previously bought from a named farm but quietly switched to cheaper suppliers without updating the menu. Restaurants that claim relationships with farms that deny ever having sold to them. Restaurants serving produce wildly out of season while attributing it to a local grower. Restaurants listing a farm that went out of business years prior. And the most insidious variant: restaurants where the named farm’s product constitutes a decorative garnish atop a plate otherwise composed entirely of commodity ingredients.

The legal framework for addressing this deception remains remarkably thin. As food law attorney Elizabeth Lizerbram noted, claims of farm-to-table fraud can theoretically be pursued under unfair competition statutes, including the federal Lanham Act, which prohibits false designations of origin in commercial advertising. Both the farmer whose name is misappropriated and the consumer who purchases mislabeled food possess standing to bring civil actions. But in practice, regulators have never defined what “local” or “sustainable” actually mean in a restaurant context, and enforcement actions remain virtually nonexistent (Lizerbram Law, 2015).

One telling anecdote from the San Diego investigation captures the dynamic perfectly. Tom Chino of Chino Farms — one of America’s most iconic small agricultural operations, whose produce Alice Waters helped make famous in the 1970s — reported that chefs routinely visit his farm, take notes, leave without purchasing anything, and then advertise his products on their menus (San Diego Magazine, 2016). The farm name has become a brand asset to be borrowed rather than a relationship to be honored.

The North Fork’s Legitimate Bounty: Where the Real Work Happens

The dishonesty of the pretenders makes the authenticity of the genuine operators all the more remarkable. Long Island’s eastern reaches — particularly the North Fork — represent one of the most concentrated legitimate farm-to-table ecosystems in the northeastern United States.

The agricultural heritage of the North Fork predates European settlement. The Corchaug people cultivated corn, tomatoes, and potatoes in what is now Cutchogue centuries before the first colonial plow broke ground in 1640 (AgroCouncil, 2024). The region’s terroir — maritime-moderated climate, deep sandy loam, ample rainfall, proximity to both the Long Island Sound and the Peconic Bay — produces conditions that rival the finest agricultural land on the Eastern Seaboard. Suffolk County is New York’s largest producer of cauliflower, cantaloupes, and pumpkins while ranking among the top three in lettuce, peppers, herbs, tomatoes, and grapes (Organic Produce Network, 2024).

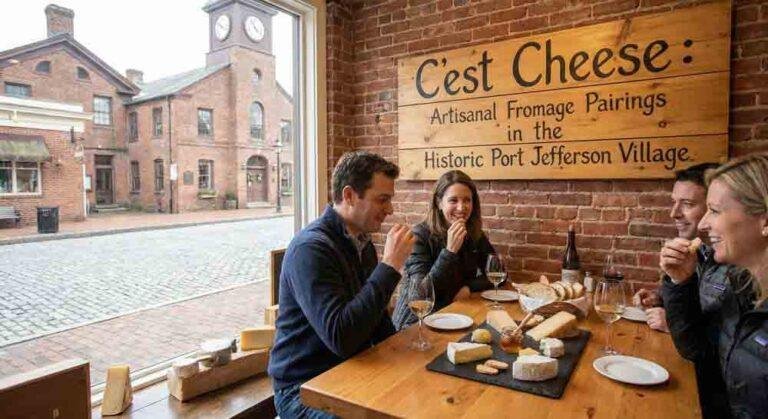

Within this landscape, a handful of restaurant operators have built businesses around genuine agricultural relationships rather than borrowed farm names. Chef Noah Schwartz of Noah’s in Greenport has maintained partnerships with Latham’s, Satur Farms, Orient Organics, and Crescent Duck Farms for over a decade, rotating his menu seasonally to reflect what these specific producers actually harvest (Chef Noah’s, 2025). North Fork Table & Inn in Southold, under Michelin-starred Chef John Fraser, sources from surrounding farms, vineyards, and fisheries, producing dishes like Jamesport Farm poached eggs and roasted Long Island duck that name their origins with verifiable specificity (North Fork Table & Inn, 2025).

In the Hamptons, operations like Amber Waves Farm maintain their own kitchen while purchasing from neighboring producers including Balsam Farms, Quail Hill, Catapano Dairy Farm, and Mecox Bay Dairy. Balsam Farms co-owner Ian Calder-Piedmonte has described this ecosystem with precision: the best chefs in the area not only purchase produce but share knowledge with growers, forming a collaborative information network where the farm tailors some of what it grows to the needs of the restaurant community (Douglas Elliman, 2025).

This is what authentic farm-to-table looks like. It is not a label. It is a logistical commitment — messy, seasonal, expensive, and relentlessly specific.

The North Shore Gap: A Diner’s Perspective from Route 25A

And here is where my quarter-century of service at the corner of Route 25A becomes relevant. The North Shore — my North Shore, the stretch from Port Jefferson through Mount Sinai and onward to Stony Brook — occupies an awkward middle ground in Long Island’s agricultural geography. We sit west of the North Fork’s farm belt but east of Nassau County’s suburban density. We are close enough to genuine agricultural operations to make local sourcing plausible, yet far enough from the East End’s Hamptons economy to lack the pricing structure that makes it financially viable.

At The Heritage Diner, I have never claimed to be a farm-to-table restaurant. What I have done, for twenty-five years, is maintain the kind of honest relationships with local suppliers that most restaurants with fancier vocabulary refuse to cultivate. I know which produce distributors actually source from Long Island growers and which merely route through Long Island warehouses. I know the difference between “locally distributed” and “locally grown.” And I know that the diner format — with its democratic pricing and its refusal to charge forty-two dollars for a salad — makes the economics of full local sourcing extraordinarily difficult without the luxury price points that the Hamptons and North Fork can command.

This is an uncomfortable truth that the farm-to-table movement has never adequately addressed. The National Restaurant Association’s 2025 State of the Restaurant Industry report found that sixty-four percent of consumers consider local sourcing important because it supports community farms (National Restaurant Association, 2025). Yet those same consumers resist the price increases that genuine local sourcing demands. The movement has created a consumer expectation without a corresponding willingness to fund it — a gap that restaurants fill with marketing language rather than actual procurement changes.

Foster in Sea Cliff represents one of the few North Shore operations approaching this challenge with intellectual honesty. Their website states plainly: “While we aren’t 100% Farm to Table, we strive to source as many of our ingredients from local farms both here in Long Island and across the tri-state area” (Foster Restaurant, 2025). That caveat — “we aren’t 100%” — is more truthful than ninety percent of the farm-to-table claims on Long Island, and it costs them nothing in customer loyalty. Transparency, it turns out, is its own form of provenance.

Dan Barber’s Reckoning and the “Third Plate” Thesis

The most intellectually rigorous critique of farm-to-table orthodoxy comes not from its opponents but from its most celebrated practitioner. Dan Barber’s 2014 book The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food argues that the movement, for all its good intentions, has enabled a form of cherry-picking that is ecologically demanding and economically unsustainable. The farm-to-table restaurant selects the glamorous cuts — the heritage tomato, the grass-fed tenderloin, the artisanal cheese — while ignoring the cover crops, the rotation grains, and the secondary products that make diversified agriculture viable (Barber, 2014).

Barber’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns, the two-Michelin-starred restaurant set on a former Rockefeller dairy farm in Pocantico Hills, operates without a fixed menu. Each evening’s dishes are dictated entirely by what the eighty-acre Stone Barns Center farm and its network of regional growers can provide that day. Some nights, different tables receive different dishes because the kitchen lacks sufficient quantity of a particular ingredient to serve it universally. Barber has developed his own grain variety — Barber wheat — with a Washington State University breeder, and co-founded Row 7 Seed Company with Cornell professor Michael Mazourek to develop vegetable cultivars selected for flavor and ecological fitness rather than shipping durability (Michelin Guide, 2024).

This is the distance between genuine practice and borrowed language. Barber employs thirty-eight cooks at Stone Barns. He has invested decades and millions of dollars in infrastructure. He breeds his own seeds. And he still considers the farm-to-table framework insufficient. The restaurant down the road that prints “locally sourced” on its brunch menu and buys its eggs from a national distributor is not operating in the same universe.

For those seeking deeper engagement with these ideas, Barber’s TED Talk on sustainable aquaculture — delivered at TED2010 and available at https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_barber_how_i_fell_in_love_with_a_fish — remains one of the most compelling articulations of what genuine ecological food production requires. His earlier TED Talk on humane foie gras production at https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_barber_a_foie_gras_parable presents an equally revelatory case study. The Netflix documentary series Chef’s Table, Season 1, Episode 2, profiles Barber’s operation at Stone Barns with the visual depth the subject deserves.

The Consumer’s Toolkit: Five Questions That Separate Farm from Fable

Having spent twenty-five years watching the restaurant industry from both sides of the pass — and having built a parallel career in bespoke craftsmanship at Marcellino NY, where the question of provenance is existential rather than decorative — I have developed what I consider the essential diagnostic for evaluating any farm-to-table claim. The methodology is borrowed from the same framework I apply to evaluating leather: trace it backward from the finished product to the raw material, and see if the story holds.

Does the menu change seasonally, or does it merely rotate? A restaurant genuinely sourcing from local farms cannot serve the same dishes year-round. If the “local heirloom tomato” appears in February, you are being told a story. Long Island’s growing season runs roughly from late May through October, with greenhouse extensions pushing into early winter for certain greens and root vegetables. Anything outside that window is either sourced from elsewhere or preserved — and if preserved, the menu should say so.

Can the staff name specific farms? Not “we source from local farms” — specific names, specific products, specific relationships. At Noah’s in Greenport, the waitstaff can tell you that the duck comes from Crescent Duck Farms and the greens from Satur Farms. At a restaurant performing farm-to-table theater, the server will offer a vague gesture toward the concept without verifiable detail.

Does the restaurant participate in the CSA and farmers’ market ecosystem? Slow Food North Shore organizes an annual Long Island CSA Fair featuring over fifteen farms. Restaurants with genuine local sourcing relationships tend to appear in these networks, often purchasing from the same farms that sell to the public. Absence from this ecosystem is not definitive, but presence is a reliable positive indicator.

Are the prices consistent with local sourcing costs? This is the uncomfortable arithmetic. A restaurant serving genuinely local, seasonal produce on Long Island cannot price its entrees at the same level as a chain restaurant serving commodity ingredients. If the prices seem too good to include local sourcing costs, they probably don’t.

Is the restaurant transparent about what it cannot source locally? Foster’s admission that it is not one hundred percent farm-to-table is the gold standard of honesty. The best operators acknowledge the limits of local sourcing — particularly for proteins, dairy, and off-season produce — rather than allowing ambiguity to imply a completeness that does not exist.

The Unseen Stitch: Why Provenance Is the Only Luxury That Matters

I return, as I always do, to the workbench. At Marcellino NY, when I select a hide of J&E Sedgwick English bridle leather for a bespoke briefcase, I know the tannery in Warwickshire where it was produced, the vegetable-tanning process that will require twelve months to complete, and the specific characteristics — the grain, the temper, the way it will accept a patina over decades of use — that distinguish it from every other hide in the world. Provenance is not a marketing term in leatherwork. It is the entire foundation of value.

The same principle applies to food, to real estate, to every domain where the question “where does this come from?” determines the difference between excellence and imitation. When Paola and I prepare to launch our boutique real estate venture in 2026, we will bring the same insistence on verifiable origin to the properties we represent — because Mount Sinai’s value, like the North Fork’s agricultural bounty, is rooted in specificity rather than abstraction.

The farm-to-table movement began as a radical act of transparency — Alice Waters at Chez Panisse in the 1970s, insisting that the origin of an ingredient was as important as the technique applied to it. Edna Lewis, whose 1976 The Taste of Country Cooking is credited by Southern Living with inspiring the modern movement, understood that food and place are indivisible. Somewhere between that founding vision and the present moment, the phrase became detached from practice, hollowed out by overuse until it signified nothing more than a willingness to pay a premium for ambiguity.

Long Island possesses every resource required to rebuild that connection between farmer and diner. Six hundred and seven farms. Thirty-four thousand acres of productive land. A direct-to-consumer agricultural economy exceeding a quarter of a billion dollars. Organizations like Slow Food North Shore and the Peconic Land Trust working to preserve agricultural land and educate the next generation of growers. The infrastructure is not the problem. The will is the problem — the collective willingness of restaurants to do the hard, expensive, logistically demanding work of genuine local sourcing rather than simply borrowing the vocabulary.

The chalkboard should mean something. After twenty-five years of feeding Mount Sinai, I can tell you that the unseen details — the ones the customer never asks about, the ones that determine whether the food on the plate has a genuine story or merely a caption — are what define a kitchen’s integrity. The same principle holds for a briefcase, a house, a life’s work. Provenance is not decoration. It is the architecture of trust.

And trust, unlike a January tomato, cannot be shipped from eighteen hundred miles away.

Peter is the owner of The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai, NY, the founder of Marcellino NY bespoke leather goods, and a North Shore real estate correspondent. He has been feeding, crafting, and building on Long Island for over twenty-five years.

Sources Cited:

- Office of the New York State Comptroller. “Agriculture Report: Long Island Experienced Gains in Farms and Farmland.” November 2024.

- National Restaurant Association. “2025 State of the Restaurant Industry Report.” February 2025.

- Reiley, Laura. “Farm to Fable.” Tampa Bay Times, April 2016.

- Johnson, Troy. “Farm to Fable.” San Diego Magazine, 2016.

- Barber, Dan. The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food. Penguin Press, 2014.

- Lizerbram, Elizabeth. “Farm-to-Table Fraud: The Legal Side.” Lizerbram Law, July 2015.

- AgroCouncil. “Agricultural and Maritime History of Eastern Long Island.” 2024.

- Organic Produce Network. “Farming on the East End of Long Island.” 2024.

- Michelin Guide. “Chef Dan Barber’s Urgent Food Revolution.” December 2024.

- Resy. “Chef Dan Barber on the Future of Food Today.” April 2024.