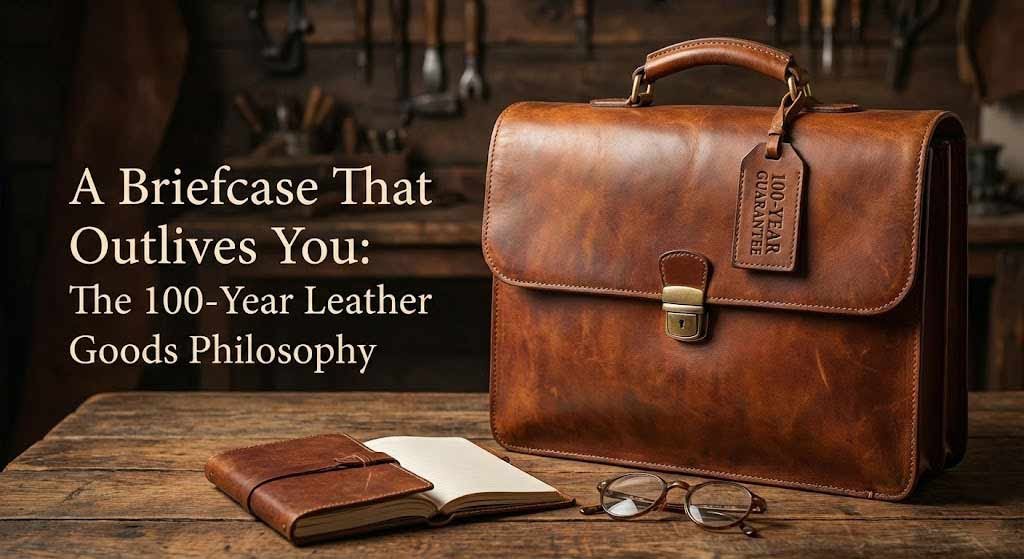

There is a moment in every craftsman’s life when the object on his bench stops being an object and starts becoming a witness. I have felt this moment thousands of times — standing in my Huntington workshop at 2 a.m., saddle-stitching the final seam on a Wallace briefcase cut from Wickett & Craig English bridle leather, the same variety of hide that once held cavalry officers steady on horseback during the First World War. The needle passes through the awl holes with a sound like a whispered promise: this will still be here when you are not. That is not poetry. That is material science. It is also, I would argue, the single most radical act of defiance a consumer can make in 2026 — buying something designed to outlast the person who buys it.

The concept feels almost seditious in an economy that has been architecturally engineered around impermanence. The fashion industry alone generates an estimated 92 million tonnes of textile waste annually, a figure the United Nations Environment Programme projects could reach 134 million tonnes by the end of this decade (UNEP, 2025). The average garment is now worn between seven and ten times before being discarded — a decline of more than 35 percent in just fifteen years (Earth.Org, 2024). Against this torrent of disposability, the idea of commissioning a single leather briefcase that your grandchildren might carry into their own careers is not nostalgia. It is insurgency.

The Chemistry of Permanence: What Separates Heirloom Leather from Everything Else

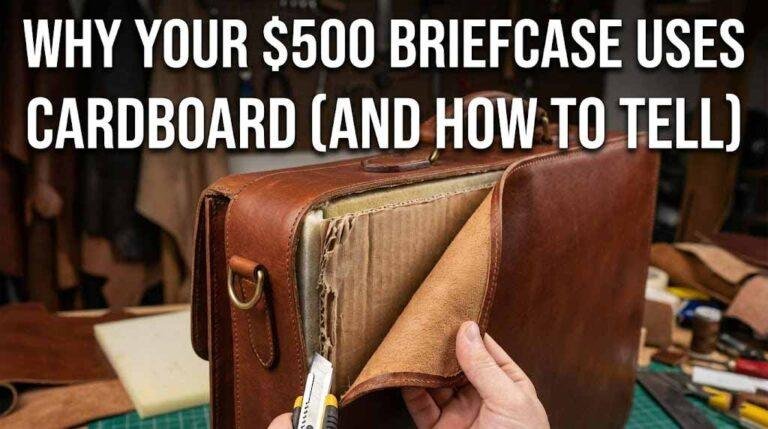

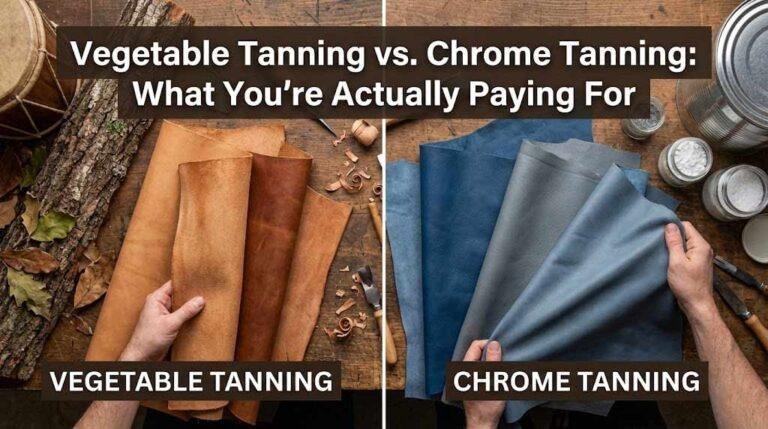

Understanding why a properly made briefcase can survive a century requires understanding what happens at the molecular level during vegetable tanning — a process that predates metalworking and remains one of the oldest chemical transformations known to civilization. At Wickett & Craig’s tannery in Curwensville, Pennsylvania — founded in 1867 and now one of the only specialty vegetable tanneries left in the United States — the transformation of a raw hide into English bridle leather takes approximately six weeks of patient, labor-intensive work (Wickett & Craig, 2024). That timeline alone should tell you something. Ninety percent of the leather on the global market is chrome-tanned, a process that uses metallic salts and can be completed in a single day (Filson Journal, 2020).

The difference is not merely philosophical. Vegetable-tanned hides are immersed in solutions derived from tree bark extracts — oak, chestnut, mimosa, quebracho — which bind with the collagen proteins in the hide, locking the natural fiber structure into a matrix of extraordinary tensile strength. The leather is then drum-dyed for deep, consistent color before undergoing “hot stuffing,” a process unique to bridle leather in which predetermined amounts of waxes, tallows, and oils are forced into both the grain and flesh sides under heat (Buckleguy, 2023). These fats don’t merely coat the surface. They saturate every fiber, creating a material that is self-maintaining — the oils continue working over time, essentially conditioning the leather from within. This is why a hundred-year-old bridle leather saddle pulled from a barn in Devon can still be supple enough to ride with after a simple wipe-down. The chemistry was designed for permanence, not planned obsolescence.

At Marcellino NY, every briefcase I build begins with this understanding. The Wallace 2220, for instance, starts its life as a side of UK-tanned English bridle leather — stiff, waxy, and marked with the characteristic “bloom” of surface wax that signals an authentic full-vegetable tannage. That bloom, which can appear as a white haze, is not a defect. It is evidence of the deep wax treatment, and it polishes away with friction, beginning the patina process that will make each bag utterly singular within months of daily carry. I source from both sides of the Atlantic — Wickett & Craig for American bridle, and traditional UK tanneries for that particular density and grain structure that the English equestrian tradition demands. This is not a marketing decision. It is a structural one. A briefcase is a load-bearing vessel. The leather must be selected for the specific stresses it will endure over decades, the way an architect selects steel grades for different positions in a skyscraper.

At the extreme end of the tanning spectrum sits J & FJ Baker & Co., Britain’s last remaining oak bark tannery, which has operated on a site in Devon, England, that has been used for tanning since Roman times. Baker’s process takes fourteen months — not six weeks, not a day, but over a year — using nothing but local oak bark and water from the stream running alongside the facility, powered by a 400-year-old water wheel mechanism (J & FJ Baker, 2024). Each bridle butt is hand-dyed with four coats of stain and finished with specially blended dubbin. The result is a leather of legendary tensile strength that Hermès selected for its exclusive “Volynka” line — a reproduction of the fabled Russian leather thought lost after the 1917 revolution, rediscovered in 1973 when the shipwreck of the Metta Catharina yielded perfectly preserved rolls after nearly two centuries underwater (Stitchdown, 2023). That is not durability. That is a kind of immortality.

The Patina of Time: Why Bespoke Leather Gets Better While Everything Else Gets Worse

There is a term in the Buy It For Life community — a movement now over 1.5 million strong on Reddit’s r/BuyItForLife — that describes the quality shared by cast-iron skillets, heritage boots, and properly made leather goods: they “get better with age” (r/BuyItForLife, 2024). This is not metaphor. It is a measurable phenomenon. Full-grain vegetable-tanned leather undergoes a process called oxidative aging, in which exposure to natural oils from human hands, sunlight, and atmospheric moisture gradually deepens the color, increases surface luster, and creates a visual record of the object’s life. Leather workers call this “patina,” borrowing the term from bronze sculpture, and it is the single quality that most dramatically separates heirloom goods from mass-market products.

I have lived this principle across every arena of my professional life. At The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai — which my family has operated for over two decades at 275 Route 25A — I watch the same transformation unfold in a seasoned cast-iron flat-top grill. The first year, the surface is merely functional. By year five, it has developed a polymerized layer of oils that no factory coating can replicate. By year twenty-five, it produces a Maillard crust on a Heritage Burger that would be physically impossible on new equipment. The grill does not degrade. It accumulates. This is the same principle that governs a Marcellino briefcase, and it is the antithesis of the disposable economy that has infected nearly every consumer category.

The philosophical implications are significant. Martin Heidegger wrote in Being and Time (1927) about the concept of “ready-to-hand” — the idea that tools reveal their true nature not through examination but through use, through becoming so integrated with the rhythms of daily life that they become extensions of the self. A mass-produced bag from a fast-fashion retailer never achieves this state. It fails before the relationship can form. A briefcase built from four-millimeter bridle leather, hand-saddle-stitched with waxed linen thread, and fitted with solid brass hardware is not merely durable enough to reach that threshold — it is designed for it. The longer you carry it, the more it becomes yours. Not in the legal sense, but in the ontological one.

The Economics of Forever: Cost-Per-Use and the Myth of Affordability

The most common objection to bespoke leather goods is price. A Marcellino Wallace briefcase begins at $3,000. A Marcellino American Alligator reaches $12,000. Against a $200 bag from a department store, the math seems absurd — until you actually do the math.

A $200 bonded-leather briefcase will last, generously, two to three years of daily professional use before the surface begins peeling, the stitching fails, or the hardware oxidizes beyond repair. Over a thirty-year legal career, that attorney will purchase ten to fifteen bags. The total cost: $2,000 to $3,000 — roughly the same price as a single bespoke briefcase that will not only survive those thirty years but emerge from them looking better than any of its disposable predecessors did on day one. This is what the BIFL community calls “cost-per-use” economics, and it is the framework that makes the entire fast-fashion model collapse under scrutiny (CostPerUse.com, 2025).

But the economic argument extends beyond the individual. The Boston Consulting Group’s 2025 textile report found that discarded clothing reached 120 million metric tons globally in 2024, with approximately 80 percent ending up in landfills or incinerators. Each year, textile waste worth roughly $150 billion in raw materials is permanently lost (BCG, 2025). The environmental cost of the disposable model is not an externality. It is the model’s primary output. When I build a briefcase that will be carried for fifty, seventy, or a hundred years, I am removing that object from the waste stream entirely. The hide was already a byproduct of the beef industry. The vegetable tanning process uses natural plant extracts rather than the chromium salts and formaldehyde compounds that contaminate waterways in industrial tanning districts from Dhaka to León. The brass hardware does not corrode. The waxed linen thread does not rot. Everything about the object is engineered for absence from the landfill.

The fast-fashion industry, by contrast, has optimized itself for the opposite trajectory. In 2024, the largest fast-fashion brands upload thousands of new items daily, producing hundreds of millions of garments per year at scales that defy comprehension (Uniform Market, 2025; Environment+Energy Leader, 2025). These are not companies that make things. They are companies that make waste — temporarily shaped into the form of things. The EU has responded with mandatory Extended Producer Responsibility for textiles, requiring manufacturers to cover the costs of collection and recycling. New York State introduced similar legislation in 2025 with Senate Bill S3217 (Environment+Energy Leader, 2025). But legislation will always lag behind the fundamental physics of the problem. The only true solution is to stop making disposable objects in the first place.

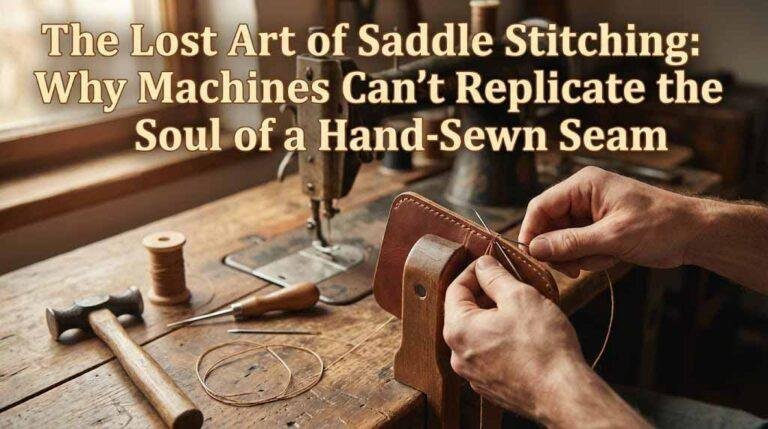

The Hands and the Hammer: Why Machine Stitching Cannot Replicate Hand-Saddlery

There is a technical reason that every Marcellino briefcase is hand-saddle-stitched rather than machine-sewn, and it has nothing to do with romance. A sewing machine creates a “lock stitch” — two threads interlocking through the material in a chain. If any single point in that chain fails, the entire seam can unravel in both directions, like a zipper in reverse. Hand saddle-stitching uses two needles and a single waxed thread, passing through each stitch hole from opposite directions. Every stitch is mechanically independent. If one breaks — which is itself rare in properly waxed linen — the adjacent stitches hold firm. The seam survives. This is why hundred-year-old equestrian tack, built using identical techniques, is still functional in working stables across the English countryside.

I learned this at the same bench where I learned everything else in this craft — alone, through repetition, through failure, through the kind of obsessive iteration that only happens when you refuse to outsource the most important steps. My workshop in Huntington, Long Island is not a factory. There is no assembly line. There are hand tools, many of them older than I am, and there is leather, and there is time. Marcellino NY has operated since 1995 — nearly three decades of refining a process that produces roughly a few dozen pieces per year. Each briefcase carries an individual serial number. Each is built to the specific requirements of its owner — size, compartment configuration, leather selection, hardware finish. When billionaire Tilman Fertitta, owner of the Houston Rockets and star of Billion Dollar Buyer, visited the workshop and purchased $140,000 worth of leather goods for his Golden Nugget Casino Hotels, he was not buying products. He was commissioning artifacts.

This is the Marcellino standard, and it is the same standard I bring to every venture I touch. At The Heritage Diner, it manifests as a refusal to use pre-formed frozen patties when hand-ground beef produces a superior product. In the real estate work that my wife Paola and I are building toward our 2026 boutique venture on the North Shore, it manifests as an understanding that the “unseen details” — the quality of construction behind the walls, the integrity of the foundation, the long-term trajectory of a neighborhood — are what determine whether a property is a home or merely a house. The principle is universal: what you cannot see is what matters most.

The Inheritance Problem: Objects, Memory, and the Transfer of Meaning

There is a photograph in my workshop of a briefcase I built years ago for a Manhattan litigator. He carried it every day for nearly two decades. When he retired, he did not throw it away or sell it on consignment. He gave it to his daughter, who had just passed the bar. The leather had darkened from chestnut to a deep cognac. The edges, burnished by years of friction against subway seats and courtroom tables, gleamed like old wood. His daughter sent me a photograph of her own, taken on her first day in court, holding the same bag her father had carried into his last. That is a one-hundred-year briefcase in the middle of its first act.

The Japanese have a word for this — wabi-sabi — the aesthetic appreciation of imperfection and transience. But the Western BIFL tradition approaches it from a different angle, one closer to the Stoic philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, who wrote in Meditations (circa 170 AD) about the importance of attending to what is “within your control” — the quality of your actions, your decisions, your commitments — and releasing attachment to what is not. Choosing to own fewer objects of greater quality is a Stoic act. It is a declaration that you will invest your resources — financial, emotional, temporal — in things that compound rather than depreciate. A Marcellino briefcase does not merely resist entropy. It converts entropy into beauty. Every scratch, every darkened crease, every worn corner is evidence of a life fully lived with that object.

This is why the Buy It For Life philosophy resonates so deeply in an era of algorithmic consumption. The movement, which began as a quiet Reddit community, has grown into a genuine cultural counterweight to the disposability complex. Its adherents are not Luddites. Many are technologists and professionals who understand systems thinking — who recognize that an economy built on perpetual replacement is a system optimized for waste, not value. When a member of r/BuyItForLife posts a photograph of a forty-year-old leather wallet or a three-generation cast-iron skillet, they are not merely sharing a product recommendation. They are making an argument about what it means to live deliberately in a world that profits from your carelessness.

The North Shore Standard: Where Craftsmanship Meets Community

Mount Sinai sits on the North Shore of Long Island, a stretch of coastline that has always understood the relationship between quality and longevity. The Gold Coast mansions of the early twentieth century were not built for a generation. They were built for dynasties. The oyster beds that once made this region famous were stewarded with a patience measured in decades, not quarters. Even the diners — those great democratic institutions of American life — survive here not through novelty but through the accumulation of trust. The Heritage Diner has served this community since 2000. It has outlasted recessions, pandemics, and the wholesale reinvention of the American dining landscape. It has done so not because it chased trends but because it refused to.

This is the principle that animates every dimension of the work Paola and I are building together. In North Shore real estate, as in leather craft and hospitality, the question is never “what is fashionable?” It is “what will still be standing?” A property’s value is not determined by its staging or its listing photographs. It is determined by the same qualities that determine whether a briefcase will survive a century: the integrity of the materials, the skill of the construction, the depth of the foundation, and the relationship between the object and the community that surrounds it. When we launch our boutique real estate venture in 2026, it will operate on these terms — the Marcellino terms — because they are the only terms that produce results worth passing down.

The convergence is not accidental. Leather, real estate, food — these are industries built on physical reality. You cannot fake the smell of a properly tanned hide. You cannot digitally replicate the satisfaction of a burger cooked on a twenty-five-year-seasoned flat-top. You cannot automate the judgment required to evaluate whether a home’s bones will hold for another fifty years. In an age when artificial intelligence can generate infinite quantities of plausible text and convincing imagery, the physical world — the world of grain and fiber and flame — becomes the last reliable theater of authenticity. What can be touched, what can be smelled, what develops a patina: this is what remains.

The briefcase on my bench tonight will ship next week to a surgeon in London. He chose the Wallace 2220 in UK Tan English Bridle with an Italian calf suede lining. The brass lock, installed with solid rivets, will click shut with a sound he will hear ten thousand times over the coming decades. The leather will darken. The suede will soften. The handle, gripped through morning commutes and conference halls and airport security lines on three continents, will mold to the exact contour of his palm. And one day, if he is fortunate and deliberate and patient — if he treats this object with the respect that its material composition demands — he will hand it to someone younger, and that person will carry forward not just a bag, but a covenant. A promise that some things are still made to endure.

That is the hundred-year philosophy. It does not require a manifesto. It requires only a needle, a hide, a hammer, and the willingness to believe that the future deserves objects worthy of inhabiting it.

Multimedia:

- The True Cost (2015) — Full Documentary on Fast Fashion — Andrew Morgan’s landmark film examining the human and environmental toll of the disposable fashion industry, essential viewing for understanding the Buy It For Life counter-movement.

- Hermann Oak Leather Company — Inside America’s Heritage Tannery — A guided tour of one of the last remaining vegetable tanneries in the United States, showing the bark-extract tanning process unchanged since 1881.

Published on The Heritage Diner Blog — heritagediner.com/blog

Written from Mount Sinai, New York — where twenty-five years of hospitality, three decades of leather craft, and a lifetime of building things that last converge at the corner of Route 25A and conviction.

Sources Cited: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2025; Earth.Org, 2024; Wickett & Craig Tannery, 2024; J & FJ Baker & Co., 2024; Stitchdown, 2023; Boston Consulting Group (BCG), 2025; Filson Journal, 2020; Buckleguy.com, 2023; CostPerUse.com, 2025; Uniform Market, 2025; Environment+Energy Leader, 2025; Heidegger, M., Being and Time, 1927; Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, c. 170 AD; r/BuyItForLife (Reddit Community); Heritage Crafts Association, UK; The Financial Times; National Restaurant Association.