There is a particular quality of morning light along the North Shore of Long Island—a silvered, salt-washed luminosity—that a person can only recognize after decades of waking inside it. I have watched that light fall across the griddle at The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai for over twenty years now, the same way it falls across the English bridle leather I work in my Huntington studio, the same way it must have fallen across the oyster beds of the Great South Bay when the Baymen hauled their wooden rakes through the shallows a century ago. That light connects us, all of us who make things by hand on this narrow spit of glacial moraine between the Atlantic and the Sound. We are Long Island’s hidden artisan economy—a dispersed, quietly defiant network of leather workers, shellfish farmers, craft distillers, vintners, blacksmiths, and cooks who have chosen, against every incentive of the modern global supply chain, to build our livelihoods around the stubborn premise that the hand-made and the place-specific still matter.

This is not a quaint story about nostalgia. It is an economic argument. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the American artisanal and specialty food sector grew at a compound annual rate exceeding six percent between 2019 and 2024 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024). New York State’s wine industry alone generates nearly $16.81 billion in total economic activity and supports over 507 wine producers (WineAmerica Economic Impact Study, 2025). The Long Island oyster industry contributes more than $30 million annually to the state economy, with projections pointing toward 100 million oysters harvested within the decade—a figure representing $200 million in economic impact (Long Island Oyster Growers Association, 2025). These are not cottage industries. They are the vanguard of a post-industrial economic model that values provenance, craft, and human skill over algorithmic scale.

The Baymen’s Renaissance: Oyster Farming and the Blue Economy

The Eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, was once so abundant in Long Island’s waters that the Lenape harvested them by the millions, leaving middens that still mark the landscape. By the mid-twentieth century, overharvesting and pollution had nearly erased them. Now, a new generation of aquaculturists is writing the next chapter. Suffolk County currently hosts approximately 45 private oyster farms and three private shellfish hatcheries, according to New York Sea Grant. In 2024, a record 9.4 million cultivated oysters were pulled from New York waters—the most ever harvested—and the trajectory is sharply upward (USDA Census of Aquaculture, 2023; Northforker, 2025).

The state has taken notice. In late 2025, New York launched its Long Island Aquaculture Infrastructure Grant Program, distributing $4 million in its first two rounds to help small-scale farmers modernize equipment and increase production capacity. Hampton Oyster Company’s Joe Finora, who farms 50 acres off the East End, invested his $100,000 grant in a high-speed digital sorting machine using vision technology—a piece of equipment that can grade up to eight oysters per second and effectively double his operation’s throughput (Dan’s Papers, 2025). Toasted Oysters Farm in Great South Bay, run by Navy veteran Mike Miezianka and paramedic Ray Smith, grew from a backyard conversation in 2020 to an operation aiming for three million oysters by the end of 2025, selling to distributors across four states (ATTRA, 2025).

I understand this trajectory intimately. When you build something with your hands—whether it is a restaurant, a briefcase, or an oyster farm—the growth curve is never vertical. It is geological. You lay down one stratum at a time. Each season at The Heritage Diner has been like a tidal cycle on the Great South Bay: you plant, you tend, you harvest, you learn what the environment teaches you. And then you do it again. The oysterman’s patience is the restaurateur’s patience. Both understand that a single adult oyster filters up to 50 gallons of water per day; that a single neighborhood diner, over 25 years, filters something equally vital through the community it serves.

Leather, Bridle, and the Marcellino Standard

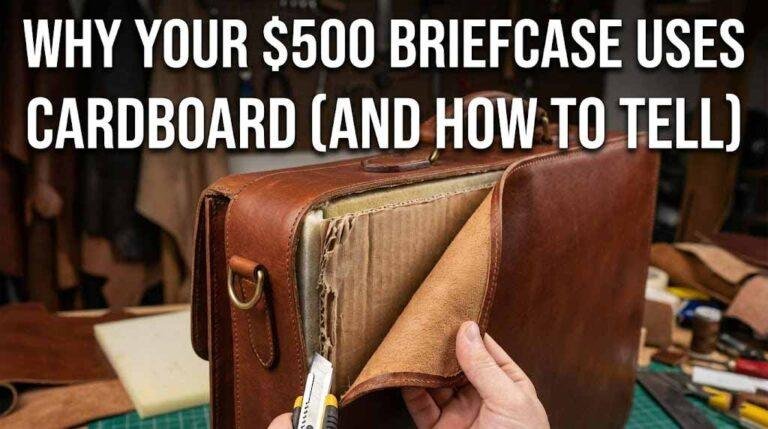

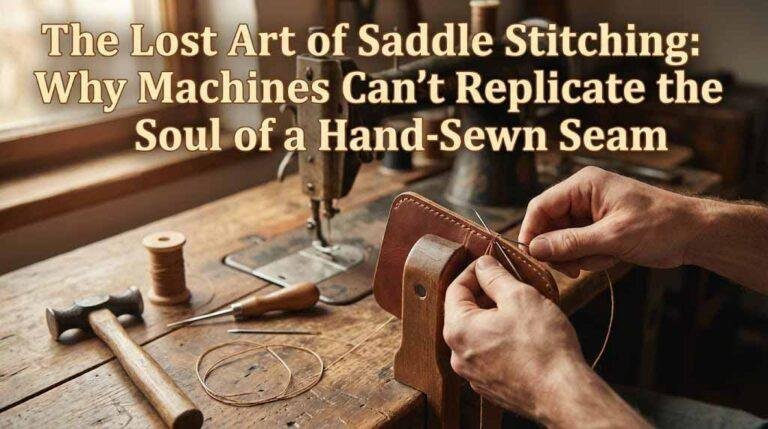

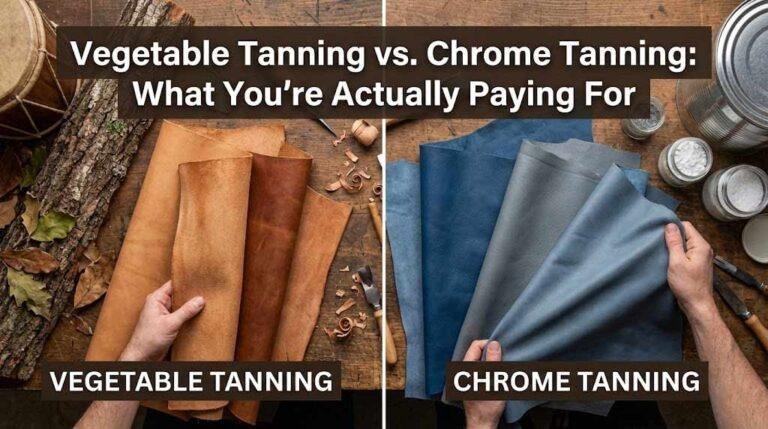

I started Marcellino NY in 1995 with a hammer, a stitching pony, and a side of Wickett & Craig vegetable-pit-tanned bridle leather—material sourced from one of the last American tanneries still using traditional bark-tanning methods. Thirty years later, the workshop in Huntington is still a one-man operation producing bespoke briefcases for lawyers, physicians, and the occasional billionaire. When Tillman Fertitta, owner of the Houston Rockets, visited the workshop and purchased $140,000 in leather goods for his Golden Nugget Casino Hotels, it was not because Marcellino NY ran a targeted ad. It was because the work speaks. A Wallace briefcase in UK tan English bridle leather, hand-saddle-stitched with linen thread and fitted with solid brass hardware, retails for $4,000. The American Alligator model commands $12,000. These are not accessories. They are instruments—built the same way they were built a century ago, with the understanding that the value of a thing is inseparable from the labor embedded within it.

This philosophy sits at the core of Long Island’s hidden artisan economy. The region has always harbored makers who refuse the logic of mass production. Lotuff Leather in Providence works from a similar premise. Frank Clegg Leatherworks in Fall River has been hand-crafting briefcases for over fifty years. But there is something specific about the Long Island maker’s relationship to New York City—a proximity that provides access to the world’s most demanding clientele without requiring the artisan to surrender the space and solitude that craft demands. I can ship a briefcase to a partner at Sullivan & Cromwell and still walk the beach at Cedar Beach the same afternoon. The old-world techniques—the beveling of edges, the burnishing of leather with beeswax and bone, the patient development of patina—require a certain quietude that Manhattan does not offer. Long Island does.

“In a world where mass-produced, cookie-cutter products reign supreme, Peter stands out as one of the few remaining Master leather briefcase makers who still uses old world techniques to carefully craft each and every one of his sculpted leather art pieces.” — Marcellino NY

The Vine, the Still, and the Fermentation of Place

Long Island’s wine country was born in 1973 when Alex and Louisa Hargrave planted the region’s first commercial vineyard in Cutchogue. Half a century later, the North Fork and Hamptons American Viticultural Areas encompass more than 60 vineyards producing world-class Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc. The maritime microclimate—tempered by the Atlantic to the south and Long Island Sound to the north—provides the kind of terroir-specific conditions that make sommeliers speak in reverential tones. The broader New York wine industry generates $2.92 billion in combined state, local, and federal taxes and drives 2.84 million tourist visits annually (WineAmerica, 2025).

The craft beverage revolution extends well beyond the vineyard. Twenty-five years ago, Long Island was home to a single craft brewery. Today, there are more than 50 stretching from Glen Cove to Greenport (LI Beer Guide, 2026). Long Island Spirits, founded in 2007 in Baiting Hollow—the island’s first craft distillery since the 1800s—distills LiV vodka from locally grown Marcy potatoes and ages Rough Rider bourbon in charred American oak. The distillery is surrounded by 5,000 acres of potato farms, a landscape that functions as both raw material supplier and aesthetic argument for the farm-to-bottle philosophy (New York Craft Spirits, 2025). Greenport Harbor Brewing, Sand City in Northport, Port Jeff Brewing—each operation is a micro-economy unto itself, creating jobs, attracting visitors, and anchoring the social life of its community.

I see the same dynamics at The Heritage Diner. Established in 2002 on Route 25A—on a site with deep roots in Long Island restaurant history, the building itself transported in pieces from Centereach where it served as the Paramount Diner—Heritage has survived every economic disruption of the twenty-first century. The pandemic. Inflation. The rise of delivery apps. The secret is the same one that sustains the vintner and the brewer: you become the place. You are not selling a commodity. You are offering a geography, a set of relationships, a sensory experience that cannot be replicated by an algorithm or a ghost kitchen.

The Economics of Provenance: Why Artisan Trades Resist Automation

The standard economic critique of artisanal production is that it does not scale. This is true—and it is precisely the point. In a paper published by the Harvard Business Review, researchers Elizabeth Currid-Halkett and others have argued that the modern “aspirational class” increasingly signals status through conspicuous production rather than conspicuous consumption—through knowing who made their goods, how, and where (Currid-Halkett, The Sum of Small Things, 2017). A Marcellino briefcase is valuable not despite its limited production but because of it. A Peeko Oyster, cultivated by Peter Stein in New Suffolk and served at Balthazar and Gramercy Tavern, derives its market premium from the specificity of its merroir—the mineral profile imparted by the Peconic Bay’s particular chemistry. You cannot factory-farm terroir.

This economic logic has profound implications for Long Island’s real estate market—a subject Paola and I are deeply immersed in as we prepare to launch our boutique real estate venture in 2026. The North Shore communities that sustain artisan economies—the Northports, the Greenports, the Mount Sinais—are precisely the communities that demonstrate the strongest long-term property value resilience. In February 2026, the median listing price for a Mount Sinai home reached $999,000, a figure that reflects not just square footage and school districts but the intangible cultural capital of a place that still has a working diner, a farmers’ market, and proximity to working waterfront (Movoto, 2026). Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “Third Place” to describe those informal public gathering spaces—neither home nor work—that anchor community life. The Heritage Diner is a Third Place. The tasting room at Greenport Harbor Brewing is a Third Place. The self-serve oyster stand on Ackerly Pond Lane in Southold is a Third Place. These are the amenities that no developer can manufacture and no tax incentive can replicate.

Peconic Escargot and the Archipelago of the Singular

Long Island’s artisan economy is not a monolith. It is an archipelago—a scattering of singular, irreplicable operations, each reflecting the obsessions of its founder. Consider Peconic Escargot, the only fresh-snail farm in America, nestled among the Christmas tree farms and apple orchards of the North Fork. Or the Old Town Arts & Crafts Guild in Cutchogue, which has showcased North Fork artisans continuously since 1948—potters, quilters, jewelers, and metalworkers whose output has no equivalent on Amazon. Or the Long Island Craft Guild, whose members include a metal sculptor whose work sits alongside Petrossian Caviar and in the three-Michelin-starred Inn at Little Washington.

Then there are the women reshaping the landscape. Little Ram Oyster Company is a women-owned and operated ten-acre underwater farm off the east end of Shelter Island, growing Eastern Oysters in Gardiners Bay. Their fully female crew produces oysters that, in their own description, “taste like vacation.” Sue Wicks of Violet Cove farms oysters using a floating cage method in Southold Bay. These operations are too small to register in most economic surveys, yet they represent the future of Long Island’s food economy—hyper-local, relationship-driven, ecologically restorative.

At Marcellino NY, I have watched a parallel phenomenon. The women’s handbag collection, Aleia, emerged from the same workshop that produces $12,000 alligator briefcases. The crossbody bags in Italian vegetable-tanned leather sell to customers who understand that a bag stitched by hand in Huntington carries a different weight—literal and figurative—than one assembled in a Guangzhou factory. The customer is buying a story. An ethic. A defiance of the disposable.

Craft as Counterculture: The Philosophical Stakes

Martin Heidegger, in his 1954 essay The Question Concerning Technology, warned that the modern technological framework transforms everything—land, labor, human relationships—into “standing reserve,” a stockpile of resources awaiting optimization. The artisan economy on Long Island is, in its bones, a refusal of that framework. When I hand-stitch a briefcase, the leather is not standing reserve. It is a collaborator. Its grain, its memory of the animal, its response to moisture and pressure—all of these properties participate in the making. The same is true for the oysterman whose crop is shaped by tide, salinity, and season; for the vintner whose Merlot is an expression of glacial soil and Atlantic wind; for the cook at The Heritage whose cast-iron skillet has been seasoned over two decades of continuous use.

The Stoics had a word for this: prohairesis—the faculty of purposeful choice. Marcus Aurelius would have recognized the artisan’s discipline: the daily decision to prioritize the excellent over the expedient, the enduring over the immediate. In a cultural moment dominated by artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making, this discipline is not merely admirable. It is radical. I use AI in my own practice—the “100 Year Briefcase” series on marcellinony.com features AI-generated images that envision how my briefcases might age across a century—but the tool serves the craftsman, not the other way around. AI can imagine the patina. Only the hand can produce it.

This is the deeper current running beneath Long Island’s artisan economy. It is not anti-technology. It is anti-reduction. It insists that human skill, local knowledge, and the irreducible particularity of place remain the primary sources of value. That a briefcase is not a briefcase is not a briefcase. That an oyster grown in the Peconic carries a different truth than one grown in the Chesapeake. That a burger seared on a Heritage griddle by someone who has cooked ten thousand burgers carries, in its crust and its juice, a competence that no ghost kitchen will ever replicate.

The Unseen Details: What a Quarter Century Teaches

I have spent 25 years learning what cannot be taught: that a neighborhood diner is not a business model but a covenant. That the smell of coffee at 6 a.m. and the clatter of a plate being set down before a regular customer constitute a form of communication more durable than any marketing campaign. That the Heritage’s sourdough sandwiches and choice-cut steaks are not menu items but arguments—arguments for attention, for care, for the proposition that a meal deserves the same seriousness as any other creative act.

The same lesson applies to the briefcase. Every Marcellino piece begins as a flat hide and becomes, through cutting, stitching, burnishing, and hardware fitting, an object with its own posture and presence. The Wallace’s knuckle handle—forged from real steel, permanently riveted to an aluminum support bar—is not decorative. It is structural and philosophical. It says: this is a thing made to be gripped, carried, used. To develop character. To outlast its maker.

And the same lesson applies to real estate. Paola and I have watched Mount Sinai evolve from a quiet North Shore hamlet into a community where families are willing to pay a significant premium for something that Zillow cannot quantify: belonging. The upcoming boutique we are developing for 2026 is rooted in this understanding. Luxury, on Long Island, is not imported. It is grown. It is fermented. It is stitched. It is served on a plate at a diner that has survived everything the twenty-first century has thrown at it, and will survive whatever comes next.

Stand at the corner of Route 25A and look east toward the Sound. You will not see the artisan economy of Long Island. You will not see the oyster farmer sorting his crop at dawn on the Great South Bay, or the brewer pulling a sample from the conditioning tank in Northport, or the leather worker in Huntington running a bone folder along the edge of a $4,000 briefcase. These operations are, by design, invisible to the casual eye. They do not advertise on billboards. They do not optimize for search. They exist in the space between the algorithmic and the authentic, between the scalable and the singular.

But they are the economy that endures. They are the economy that gives a place its character, its gravitational pull, its reason for being more than a coordinate on a GPS screen. Long Island’s hidden artisan economy is not a relic of the past. It is the infrastructure of the future—a future in which the question is not how fast or how much, but how well and for whom. The Heritage Diner will still be here, casting its light across Route 25A. The oyster farmers will still be on the water. The leather will still be curing. And the unseen details—the ones that define a masterpiece—will still be the only ones that matter.

Recommended Viewing

▶ Watch: NBC TODAY – How a Long Island Community Is Giving a Boost to Oyster Population

▶ Watch: PBS Women of the Earth – How This Oyster Farmer Is Reinventing Aquaculture

The Heritage Diner · 275 Route 25A, Mount Sinai, NY 11766 · Est. 2002

Marcellino NY · American Briefcase Maker · Craftsman Since 1995 · marcellinony.com

© 2026 Heritage Diner Blog. All rights reserved.