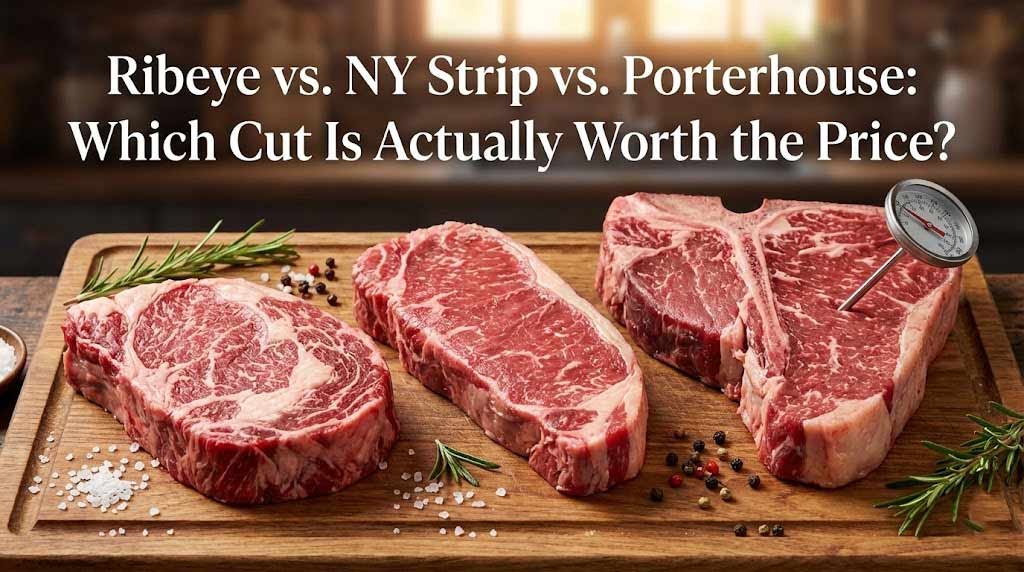

The moment you open a steakhouse menu and your eyes land on that price list, a familiar tension emerges. The ribeye. The New York strip. The porterhouse. Three names that command three distinctly different prices, yet evoke passionate disagreement among meat lovers about which offers the superior value. After three decades of Delmonico’s introducing the nation to fine steak dining in 1837, and two centuries of subsequent steakhouse culture refining these cuts into art forms, the question persists unresolved. Which of these three premium beef selections justifies its price point? Which truly delivers the most meat for your money? And perhaps most importantly, which aligns with your personal taste and eating philosophy?

This isn’t merely an academic exercise in beef taxonomy. The financial differences are real. According to the USDA National Retail Report, boneless ribeye steaks range from $10.93 to $13.40 per pound, while New York strip steaks typically cost $10-15 per pound, and porterhouse steaks—the largest and most expensive—command between $10.56 and $11.16 per pound depending on market conditions and retail location (USDA Retail Report, 2025). These price variations reflect not mere marketing; they represent genuine anatomical differences, cooking behaviors, and eating experiences that separate a sophisticated carnivore’s optimal choice from a wasted expenditure. The answer to which cut offers the best value depends entirely on understanding what you’re actually buying, what happens to that meat during cooking, and whether the eating experience aligns with your priorities.

Anatomy and Sourcing: Where These Cuts Come From

Understanding value begins with understanding origin. The ribeye emerges from the rib section of the cow, specifically ribs 6 through 12, an area of the animal that receives minimal muscular exercise throughout the cow’s life. This lack of movement permits extensive intramuscular fat development—the marbling that defines ribeye character. The cut typically includes two main muscles: the longissimus dorsi (the “eye” of the ribeye) and the larger, fattier spinalis dorsi (the “cap” of the ribeye), which many connoisseurs consider the most delicious single bite available in beef (Snake River Farms, 2025).

The New York strip, by contrast, comes from the short loin section, located behind the ribs and before the thigh. The short loin also experiences minimal movement, making this muscle similarly tender, but the anatomical differences matter substantially. The strip steak consists almost entirely of the longissimus dorsi muscle, the same muscle that appears in one half of a porterhouse or T-bone. This single-muscle construction creates uniformity in texture and flavor, distinct from the ribeye’s dual-muscle composition (Steak University, 2025).

The porterhouse represents a fundamentally different value proposition: two steaks in one. According to the definition that distinguishes it from its smaller cousin the T-bone, a porterhouse must contain a tenderloin portion (filet mignon) larger than a U.S. quarter, cut from the short loin and separated from the strip steak by a substantial T-shaped bone (derived from the cow’s lumbar vertebrae). This bone structure means that a porterhouse weighing 16-24 ounces contains two distinct muscle groups operating according to different flavor and textural profiles, creating what amounts to two dining experiences within a single steak (Evermore Farm, 2020).

The anatomical distinction creates an immediate pricing consideration. At similar per-pound prices, a porterhouse provides greater total weight, yet contains a larger proportion of inedible bone (approximately 20% of the porterhouse’s weight), which complicates the value calculation. A porterhouse’s total edible meat yield may actually be less than a similar-weight ribeye or strip despite the higher total weight, a reality that sophisticated meat buyers recognize when comparing price tags (Steak University, 2025).

Marbling, Fat Content, and Flavor: The Foundation of Taste

The most significant operational difference between these cuts lies in fat distribution, which fundamentally determines both flavor and cooking behavior. The ribeye contains substantially more intramuscular fat—approximately 20 grams of fat per 4-ounce serving compared to the New York strip’s approximately 5-6 grams per 4-ounce serving. This 300% fat difference doesn’t merely influence calorie content; it transforms the entire eating experience (Lara Clevenger, 2024).

That intramuscular fat, called marbling, dissolves during cooking at temperatures around 130-140°F, basting the meat from the inside out and creating the melt-in-your-mouth texture ribeye aficionados pursue. The fat also carries flavor compounds—lipophilic molecules that human taste receptors detect as savory, rich, and indulgent. A ribeye cooked to medium-rare achieves a buttery, almost luxurious mouthfeel that represents the fundamental appeal of the cut. For this reason, ribeye commands a slight price premium over similarly-sized strip steaks: consumers recognize that the marbling density justifies the additional cost (Cross Creek Ranch Premium Meats, 2025).

The New York strip’s leaner profile—with its fat concentrated primarily in a defined strip along one edge—creates a different flavor narrative. The strip steak’s taste emerges from the meat itself rather than fat basting, resulting in what meat professionals describe as “bold” or “pronounced” beef flavor. The muscle fibers remain tighter even during cooking, creating what some describe as a satisfying chew rather than the pure tenderness of a ribeye. For steak lovers who prioritize the taste of beef itself over maximum juiciness, the strip steak’s leaner profile represents an advantage rather than a liability, yet the market prices it lower than ribeye, suggesting that juiciness commands greater consumer preference (Chowhound, 2023).

The porterhouse presents a fat profile complexity unique among these three cuts. The strip side contains moderate marbling and behaves similarly to a standalone strip steak. The tenderloin side, however, represents one of the leanest cuts available on a beef animal. This creates an internal contradiction: one half of the porterhouse delivers concentrated juiciness while the other half offers delicate, lean tenderness. Some diners view this duality as perfect balance—the best of both worlds on a single plate. Others find the textural and flavor contrast jarring, preferring the consistency of a single-muscle cut (Snake River Farms, 2025). This philosophical divide explains why porterhouse pricing remains competitive despite its larger size: not all consumers value the two-steak experience, dampening demand relative to the ribeye’s straightforward luxury positioning.

Cooking Behavior: Why Technique Determines Success

The cooking properties of these three cuts diverge so substantially that technique becomes almost as important as sourcing quality. The ribeye’s high fat content provides forgiveness during cooking—that fat renders gradually, protecting the interior from overcooking even as the exterior develops a crust. A ribeye cooked to medium or even medium-well remains more tender than a strip steak cooked to the same doneness, because the intramuscular fat prevents the muscle fibers from contracting into toughness (DC Steakhouse, 2023). This forgiving quality permits the classical steakhouse approach: sear in a screaming-hot cast iron skillet at high heat (400-425°F) for 3-4 minutes per side, flipping only once, and removing from heat when an instant-read thermometer reads 120-125°F for medium-rare (Misen, 2024). The ribeye’s fat essentially insurance policy allows confidence in straightforward technique.

The New York strip demands greater precision. Because the leaner muscle cannot rely on fat to prevent overcooking, timing becomes critical. Overcook a strip steak by just 5°F, and the muscle fibers contract excessively, creating a tough texture that can’t be recovered. The ideal technique requires higher initial heat (similar to ribeye treatment) but with obsessive temperature monitoring and removal at exactly 120-125°F for medium-rare, no margin for error (New York Strip vs. Ribeye, 2025). Interestingly, many contemporary chefs advocate for the “Just Keep Flipping” method on strip steaks, flipping every 20-30 seconds, which builds a more even crust while reducing the temperature gradient that traditionally creates gray, overcooked bands beneath the surface (Misen, 2024).

The porterhouse introduces complexity that tests even experienced cooks. The T-shaped bone conducts heat unevenly, meaning different sections of the steak finish cooking at different rates. The strip side, being meatier and fattier, requires different treatment than the tenderloin side, which cooks faster and benefits from protection. The traditional steakhouse approach—starting with a screaming sear then finishing in a lower-temperature oven—works for porterhouse but requires attention to ensure both sides achieve target doneness simultaneously. The reverse-sear method (slow-cooking at 225-250°F until 10-15°F below target temperature, then searing in a 500°F+ cast iron skillet for 1-2 minutes per side) actually proves superior for porterhouse, because the low-heat phase allows the tenderloin and strip to reach temperature together despite their anatomical differences, and the dry surface achieved during low-heat cooking enables a more efficient Maillard reaction during the final sear (Steak University, 2025). This explains why restaurants with steakhouse reputations typically favor the reverse-sear method for large cuts.

Watch this comprehensive demonstration of reverse-sear technique: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKPNmqgSyAw

The Maillard Reaction: Understanding What Creates Flavor

The development of the crust—that essential element separating a steakhouse steak from a merely cooked steak—depends on a specific chemical reaction that occurs at precise temperatures. The Maillard reaction, a non-enzymatic browning process where amino acids and reducing sugars interact, creates hundreds of flavor and aroma compounds when surface temperature exceeds 285°F (140°C). This isn’t caramelization (which involves only sugars); it’s a far more complex process that produces the characteristic savory, umami-rich flavors that define exceptional steak (FireBoard Labs, 2024).

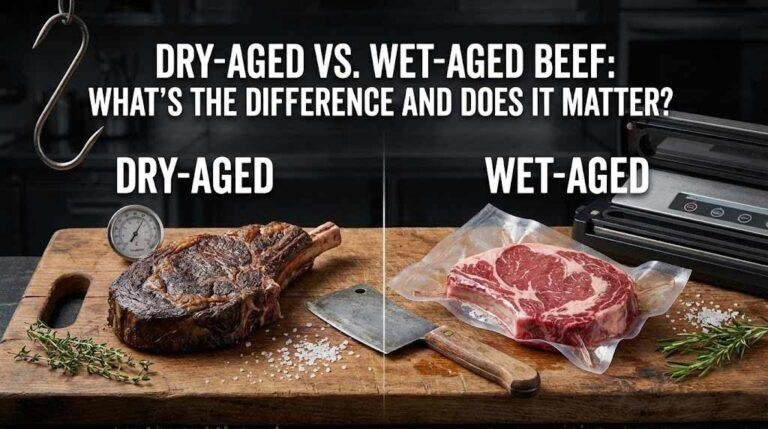

The Maillard reaction requires three conditions: high heat, adequate time, and most critically, a dry surface. Moisture prevents the surface temperature from exceeding 212°F (the boiling point of water), so a wet or damp steak surface essentially starts the browning race uphill. This explains why professional cooks obsessively pat steaks dry with paper towels before cooking and why bringing steak to room temperature (allowing surface condensation to evaporate) improves results (Traeger, 2025).

The reverse-sear method, increasingly popular among home cooks and professionals, elegantly solves this problem. The low-temperature cooking phase (225-250°F) slowly brings the steak to target internal temperature while simultaneously evaporating surface moisture. By the time the steak reaches the searing stage, the surface has already shed its moisture and sits primed for rapid browning. A 1-2 minute sear in a 500°F+ pan creates a deeply caramelized crust through efficient Maillard browning (BBQ Report, 2025). Interestingly, reverse-seared steaks typically develop superior crusts compared to traditional searing because the moisture issue is completely eliminated, allowing the browning to proceed unimpeded at full efficiency.

The ribeye’s high fat content presents a unique searing challenge: fat drippings can cause flare-ups on a grill or create uneven browning in a skillet. However, the rendered fat also contributes basting that flavors the developing crust with meat juices. The strip steak, being leaner, poses fewer flare-up concerns but requires more precise heat management to prevent the exterior from burning while the interior reaches target temperature (Holy Grail Steak Co., 2023). The porterhouse requires the most attention precisely because different sections demand different searing approaches—the thicker strip side benefits from sustained high heat, while the thinner tenderloin side risks overcooking with aggressive searing (Hey Grill Hey, 2024).

Practical Value Analysis: Cost Per Pound vs. Actual Enjoyment

When comparing value across these three cuts, the analysis becomes more nuanced than simple per-pound pricing. A typical ribeye steak weighs 10-14 ounces at approximately $12-16 per pound, totaling $30-45 per steak depending on location and quality grade. A comparable New York strip runs 10-14 ounces at approximately $10-15 per pound, totaling $25-42 per steak. A porterhouse, weighing 16-24 ounces at similar per-pound pricing, creates apparent value—$40-60 per steak appears more expensive but offers greater raw weight.

The complication emerges when accounting for inedible components and personal preference. A porterhouse’s bone represents 15-20% of its weight—a substantial portion providing no meat. The actual edible muscle content of a 20-ounce porterhouse might represent only 14-16 ounces of actual meat, placing the true per-pound meat cost higher than initially apparent. Furthermore, if you dislike the textural contrast between filet and strip within a single steak, you’re paying premium pricing for an eating experience that frustrates rather than satisfies. In this calculus, a ribeye or strip steak sized to your appetite represents superior value (Evermore Farm, 2020).

The cooking technique required for each cut introduces a hidden value component. If your kitchen equipment or expertise favors straightforward, high-heat searing without temperature monitoring, the ribeye’s forgiving nature translates to fewer burned steaks and more consistent successes. If you’ve invested in precise thermometers and understand reverse-sear methodology, the strip steak’s lower price combined with your technical expertise delivers superior per-dollar enjoyment. The porterhouse demands the most technique investment and fails to reward sloppy execution, making it arguably the worst value choice for home cooks unwilling to commit to reverse-searing (Cross Creek Ranch Premium Meats, 2025).

Historical Context: How Delmonico’s Shaped Modern Steak Culture

The contemporary steakhouse landscape owes everything to Delmonico’s Restaurant, which opened in 1827 as a pastry shop before evolving into America’s first fine dining establishment by 1837. Under the culinary leadership of Chef Alessandro Felippini, Delmonico’s developed the “Delmonico Steak”—a thick-cut ribeye that became legendary in American culinary history (Delmonico’s Official History, 2025). The innovation wasn’t merely the steak itself; it was Delmonico’s pioneering decision to permit customers to order from a menu à la carte rather than accepting whatever was prepared that day—a revolutionary concept at the time (Simple English Wikipedia, 2025).

This historical context illuminates contemporary steak culture. The New York strip steak, sometimes called the Delmonico steak in various regions, originated from the same steakhouse innovation but represents a different cut from what Delmonico’s originally served. The confusion persists because the “Delmonico steak” name became applied to various premium thick-cut beef, primarily from the rib section, rather than referring to a specific anatomical cut (Acabonac Farms, 2024). Modern Delmonico’s restaurant continues serving a prime cut ribeye at their Wall Street location, maintaining the lineage of that original vision.

Understanding this history reveals that premium steak culture didn’t emerge from some ancient refinement of butchery knowledge. Instead, it emerged from restaurateurs recognizing that quality ingredients, precise technique, and straightforward preparation—salt, pepper, high heat—could create dining experiences worthy of premium pricing. The three cuts discussed here represent the logical outcome of that philosophy: cuts from low-movement sections of the animal (ensuring tenderness), butchered and priced to reward quality-conscious consumers willing to pay for superior materials and careful preparation.

This historical recognition matters for contemporary value assessment. A superior-quality New York strip steak from a knowledgeable butcher will outperform a mediocre ribeye from a supermarket every single time, because sourcing quality exceeds cutting technique in importance. The most valuable purchase considers not just the cut, but the specific animal’s diet, age, and handling—factors that influence tenderness and flavor more substantially than the choice between rib or loin (Meat Dudes, 2025).

The three premium steaks examined here offer legitimate paths to exceptional dining, each serving different preferences and priorities. The ribeye commands its premium position through unmatched juiciness and forgiving cooking behavior, rewarding both precision and imprecision with consistent results. The New York strip delivers concentrated beef flavor and technical challenge, appealing to purists who view fat as optional rather than essential. The porterhouse provides duality and pageantry, offering two distinct experiences within a single impressive cut, though at the cost of complexity and reduced appeal to customers who value consistency.

The honest value assessment concludes that no single cut universally represents “best value.” Instead, value emerges from alignment between cut characteristics, your cooking methodology, and your eating preferences. A home cook with a sharp thermometer and reverse-sear discipline might achieve the greatest satisfaction from a strip steak at $10 per pound. A backyard griller without temperature monitoring will suffer fewer failures with a forgiving ribeye at $13 per pound. A diner seeking spectacle and willing to invest technique in achieving perfect doneness on both sides of a bone might legitimately prefer a porterhouse’s theater despite its premium price. The expensive steakhouse experience—where professional equipment, deep expertise, and premium sourcing converge—permits all three cuts to deliver transcendent meals, justifying their premium pricing through factors entirely beyond the meat itself.

The question “which cut is actually worth the price?” ultimately resolves not through abstract analysis but through honest self-assessment. What do you actually want from steak? Pure juicy indulgence? Concentrated beefy flavor? Dramatic presentation? Once you’ve answered that question truthfully, the value calculation becomes clear, and the market pricing reveals itself as either justified or arbitrary based on your specific preferences rather than objective superiority.

Explore how Long Island’s best steakhouses source and prepare these cuts to understand how professional technique amplifies quality materials. Consider also understanding steak grades and USDA prime standards to recognize how sourcing quality influences value more substantially than cutting preferences.