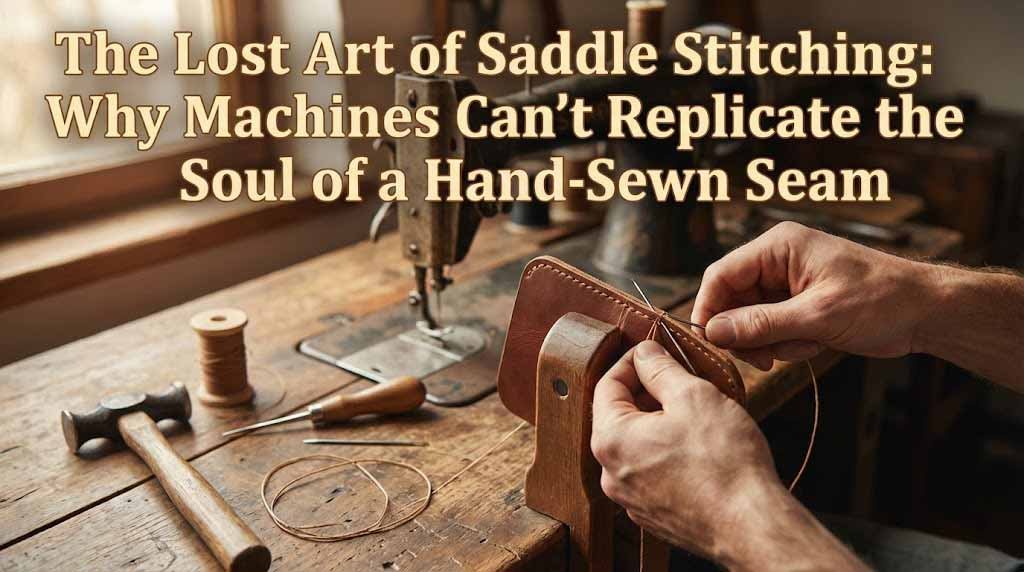

There is a moment—imperceptible to anyone who hasn’t spent a decade at a stitching pony—when the awl finds the leather’s grain and the resistance shifts from defiance to acceptance. The blade enters not because you forced it, but because you understood the hide. You read its density the way a surgeon reads an X-ray or a seasoned restaurateur reads the silence of a dining room at 7:14 on a Friday evening, that half-second before the flood. I have spent twenty-five years behind the pass at The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai, and another decade-plus at my bench crafting English bridle leather briefcases under the Marcellino NY name. In both disciplines, the same truth recurs with stubborn persistence: the things that matter most are the things no machine can do. The saddle stitch is one of those things. It is the oldest, strongest, most elegant method of joining two pieces of leather ever devised, and despite two centuries of industrial sewing innovation, not a single machine on earth can reproduce it. This is the story of why.

The Anatomy of an Ancient Stitch

The saddle stitch predates the industrial revolution by at least three centuries. Its origins lie in European saddlery workshops—principally in England and France—where harness makers and bridle craftsmen needed seams that could endure the full kinetic violence of a horse at gallop without separating (Waterer, Leather in Life, Art and Industry, 1946). The technique is deceptively simple in description: two needles, one continuous length of waxed linen thread, and a series of pre-punched holes through which both needles pass in opposite directions, crossing inside the leather and locking each stitch independently of the next.

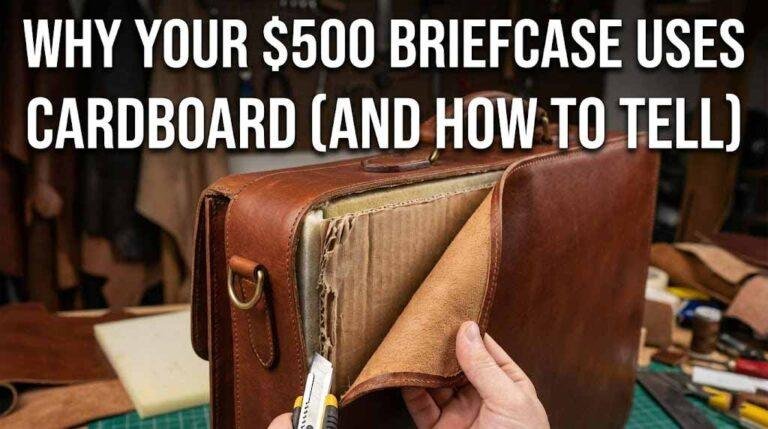

What separates the saddle stitch from every machine-generated seam is structural. A sewing machine—even a top-of-the-line Juki or Consew industrial unit—produces a lock stitch. One needle drives thread down through the material while a bobbin underneath loops a second thread around it, creating an interlocking chain. If a single stitch in that chain is cut or abraded, the entire seam can unravel in seconds, the way a single pulled thread will dismantle a cheap sweater. The saddle stitch operates on an entirely different mechanical principle. Because each stitch is created by two independent passes of thread through the same hole, every stitch is structurally autonomous. Cut one, and nothing happens. The adjacent stitches actually tighten under tension, compensating for the breach (Tandy Leather, “Saddle Stitching Technique Guide,” 2021). This is why centuries-old saddles in museum collections still hold together while factory-sewn leather goods from five years ago sit in landfills.

The Tooling: Pricking Irons, Awls, and the Geometry of Intention

Before a single stitch is sewn, the craftsman’s relationship with the leather begins at the marking stage. At the Marcellino NY bench, I use French-style pricking irons—multi-toothed steel instruments that resemble a delicate fork—to mark the stitch line along a grooved channel cut into the surface of the leather. The groover itself serves a dual purpose: it creates a recessed track so the finished thread sits flush with the surface rather than proud of it, and it provides a visual guide that keeps the stitch line parallel to the edge at a consistent distance, typically three to five millimeters for fine goods (Armitage Leather, “Traditional Saddle Stitch Course Curriculum,” 2024).

The pricking iron marks the spacing—seven stitches per inch for my briefcases, nine for smaller goods like cardholders and watch straps—but it does not pierce the leather completely. That is the work of the awl, and this is where the craft ascends from technique into art. The diamond-point awl, honed to a mirror polish before each session, must be driven through the full thickness of the material at a consistent angle, following the diagonal orientation established by the pricking marks. The angle matters enormously. It determines whether the finished stitch line presents as a clean, angled series of dashes—the signature visual language of bespoke leatherwork—or a chaotic scatter of inconsistent marks.

As Nigel Armitage, the British master saddler and educator who has trained leatherworkers for over thirty years, has demonstrated extensively in his instructional work, mastering the awl is the single most difficult element of saddle stitching. His courses at Armitage Leather focus obsessively on this one tool, because every other element of the stitch depends on the precision of the hole it creates (Armitage Leather, 2024). I have found this to be profoundly true. You can thread needles perfectly, wax your linen immaculately, and tension every pull with laboratory precision—but if your awl work is inconsistent, the finished product will betray you.

Why No Machine Can Do This

The question deserves a precise answer, not a romantic one. Industrial sewing machines cannot produce a saddle stitch because of a fundamental mechanical limitation: they operate from one side of the material only. A machine needle descends through the leather, catches a bobbin thread underneath, and returns. It cannot simultaneously pass two threads through the same hole from opposite directions—the defining action of the saddle stitch—because that would require two needle mechanisms operating in coordinated opposition through a single point. No such machine exists in commercial production.

Some manufacturers have marketed “saddle stitch” machines that approximate the visual appearance—principally the angled stitch line—using modified lock-stitch or chain-stitch mechanisms. These are marketing fabrications. The Craft Industry Alliance reported in 2022 that the proliferation of “hand-stitched look” machines in Chinese and Southeast Asian factories has created a global market flooded with goods that mimic the aesthetic of handwork while delivering none of its structural advantages. The tell is always the reverse side: a true saddle stitch produces a near-identical pattern on both faces of the leather, front and back. A machine stitch, no matter how cleverly engineered, will always show a distinct difference between the needle side and the bobbin side (Fine Leatherworking, “Saddle Stitching Video Round Up,” 2024).

But the machine’s failure is not merely mechanical. It is also adaptive. When I stitch a Marcellino briefcase gusset—where the leather curves and the thickness changes as panels overlap—I am constantly adjusting. The angle of the awl shifts. The tension on each pull varies by fractions of a pound. I compensate for the hide’s inconsistencies: a slightly thicker section near the backbone, a softer region near the belly, a knot where a healed scar changed the fiber structure. A machine cannot read these variations. It applies the same force, the same speed, the same tension to every stitch regardless of what the leather is doing beneath the needle. The result, over years of use and stress, is the difference between a seam that endures and a seam that fails.

The Thread: Waxed Linen and the Chemistry of Longevity

Thread selection is not an afterthought—it is an engineering decision. At Marcellino NY, every briefcase is stitched with waxed linen thread, a material whose provenance in fine leatherwork stretches back to at least the seventeenth century. Linen thread—spun from flax fiber—possesses a natural tensile strength that exceeds cotton and most synthetics of comparable gauge. When saturated with beeswax or a beeswax-rosin compound, the fibers swell slightly, filling the stitch hole more completely and creating a near-waterproof seal at every point of entry and exit.

The waxing process also serves a frictional purpose. As each stitch is pulled tight, the wax creates micro-adhesion between the thread and the interior walls of the leather channel. Over time, this bond strengthens rather than weakens—the opposite of what occurs with synthetic polyester thread, which tends to relax and lose tension as its molecular structure fatigues under UV exposure and mechanical cycling (Journal of the American Leather Chemists Association, Vol. 114, 2019). Hermès, the French luxury house that remains the most visible practitioner of saddle stitching at scale, uses waxed linen exclusively for hand-stitched seams, recognizing that the thread’s relationship with the leather is as important as the stitch geometry itself (Permanent Style, “Hermès: How Leather Goods Are Made,” 2011).

I draw a parallel to what happens at The Heritage Diner with seasoning. A cast-iron skillet that has been properly seasoned over decades develops a polymerized surface that no factory coating can match—not because the chemistry is unknowable, but because the process requires time, heat, fat, and repetition in proportions that cannot be industrialized. Waxed linen in a saddle stitch is the same. Its performance improves with age. The briefcase I made for a Manhattan attorney nine years ago has stitching that is stronger today than the day I cut the thread.

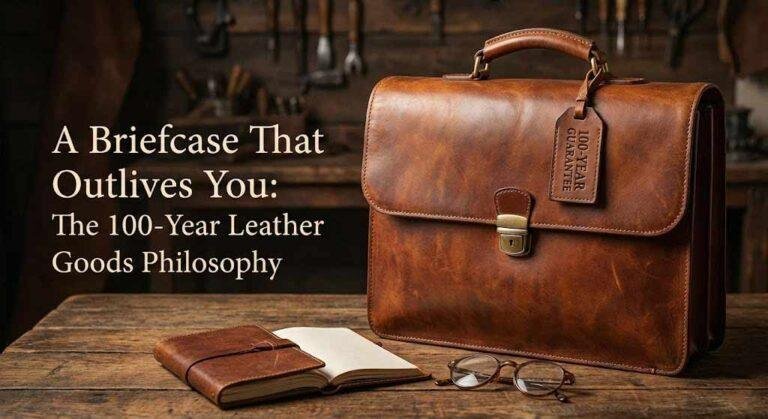

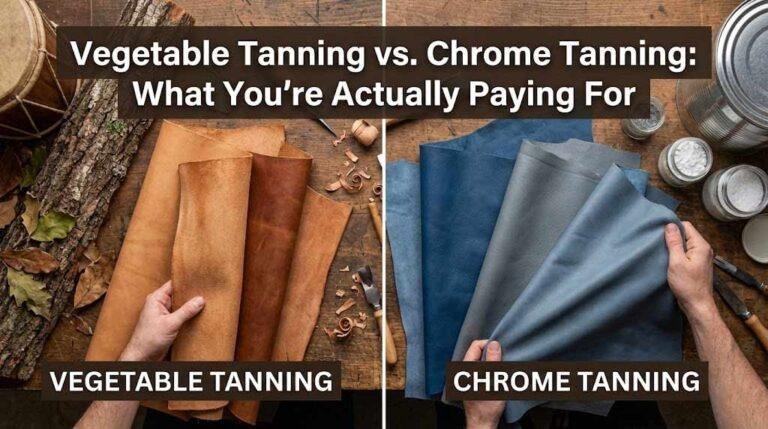

English Bridle Leather: The Material That Demands the Method

Not all leather deserves a saddle stitch, and not all stitching methods deserve English bridle leather. The two exist in a symbiotic relationship that has been refined over centuries of equestrian tradition. English bridle leather is vegetable-tanned—processed using natural bark extracts, principally mimosa and quebracho, over a period of weeks rather than the hours required by chrome tanning (Wickett & Craig Tannery, “English Bridle Leather Specifications,” 2023). After tanning, the hides are hot-stuffed with a proprietary blend of tallows, waxes, and oils that penetrate the full cross-section of the material, producing a leather that is simultaneously firm and pliable, weather-resistant and breathable.

This is the leather I chose for every Marcellino NY briefcase, and the reason is inseparable from the saddle stitch. Because English bridle leather is vegetable-tanned, its fiber structure is tighter and more uniform than chrome-tanned alternatives. This density means the awl produces a cleaner hole, the thread seats more precisely, and the finished stitch compresses into the grooved channel with a mechanical snugness that chrome-tanned leather—softer, spongier, more forgiving but also less precise—simply cannot achieve. The Walsall Leather Skills Centre in England, one of the last dedicated training institutions for traditional saddlery, has noted that the pairing of English bridle leather with the saddle stitch represents the apex of structural integrity in hand-sewn goods (Walsall Leather Skills Centre, “A Beginner’s Guide to Saddle Stitching,” 2025).

The patina question is equally relevant. English bridle leather develops a deep, burnished surface character over years of handling—what Marcellino NY has long called “The Patina of Time.” That patina tells the story of the object’s life. Every briefcase I deliver will look fundamentally different in five years than it does on delivery day, and that transformation is not degradation; it is maturation. The saddle stitch participates in this evolution. As the thread and leather age together, the wax integrating further into the fiber, the stitch line develops a visual depth—a settled, embedded quality—that machine stitching, with its synthetic thread and shallow penetration, never achieves.

The Philosophical Dimension: Heidegger’s Hammer and the Ethics of Making

There is a reason I keep a copy of Heidegger’s Being and Time on the same shelf as my pricking irons. The German philosopher’s concept of Zuhandenheit—”readiness-to-hand”—describes the state in which a tool becomes so thoroughly integrated into the craftsman’s intention that it disappears from conscious awareness. The hammer, Heidegger argued, is not truly understood by staring at it; it is understood by driving nails until the act of hammering becomes transparent, until the tool and the hand and the purpose merge into a single flow of directed action (Heidegger, Being and Time, 1927).

This is precisely what happens at the stitching pony after years of practice. The awl, the needles, the thread, the tension of the pincer between my knees—they cease to be objects and become extensions of intention. I do not think about the stitch. I think about the briefcase. I think about the attorney in Midtown who will carry it into depositions for the next thirty years, about the surgeon on the Upper East Side who needs a bag that communicates the same precision she brings to an operating room. The stitch is the means through which that intention becomes material reality. A machine cannot have intention. It can have programming, calibration, and quality control parameters. But it cannot understand why a seam matters, and that understanding—invisible, unmeasurable—is what separates a Marcellino briefcase from the thousands of “hand-stitched look” bags that fill the display cases of department stores from SoHo to Short Hills.

This philosophical dimension connects all three of my worlds. At The Heritage Diner, after twenty-five years, I do not think about the mechanics of running a kitchen during a Friday dinner rush; I think about the experience of the family at table twelve who have been coming here since their kids were in car seats. My wife Paola, who is preparing to launch our boutique real estate venture in 2026, understands this same principle in her domain: the best properties on the North Shore are not sold on square footage and school district ratings alone—they are sold on the invisible quality of belonging, the sense that a house will become a home in a way that a spreadsheet cannot quantify. The saddle stitch is the leatherworker’s version of this truth. It is the unseen detail that defines the masterpiece.

What We Lose When We Stop Teaching It

The saddle stitch is endangered. Not in the way of a species facing extinction—there are still practitioners, still teachers, still ateliers where the method is transmitted with reverence—but in the way of a language losing its native speakers. The National Endowment for the Arts reported in 2023 that enrollment in traditional craft apprenticeships across the United States has declined by 34% since 2010, with leatherwork among the most affected disciplines. The economics are punishing: a saddle-stitched briefcase takes forty to sixty hours of hand labor, and the pricing required to sustain a living wage at that pace puts the finished product out of reach for all but the most deliberate buyers.

And yet. The search data tells a different story. Google Trends analysis shows that queries for “saddle stitch leather,” “hand-stitched briefcase,” and “bespoke leather goods” have increased steadily since 2019, accelerating sharply during and after the pandemic years (Google Trends, 2024). There is a counter-movement underway—quiet, determined, largely driven by consumers who have grown exhausted by the disposability of mass-market goods and are seeking objects that carry the weight of human intention. This is the same impulse that has kept The Heritage Diner alive for a quarter century while chain restaurants rise and fall around us on Route 25A. It is the same impulse that drives families to seek out Paola for help finding a home on the North Shore rather than scrolling through algorithmic listings. People want to be known. They want their objects—their meals, their homes, their briefcases—to know them back.

The saddle stitch is, finally, an act of resistance. Not against technology per se—I use digital calipers at my bench and point-of-sale systems at the diner, and I regard artificial intelligence as one of the most powerful tools for human refinement ever created. The resistance is against the assumption that efficiency is the highest value, that speed and scale are synonymous with progress, and that anything a human hand can do, a machine will eventually do better. The saddle stitch stands as quiet, permanent proof that this assumption is wrong. Two needles. One thread. A thousand years of accumulated knowledge passing through a single hole in a piece of English bridle leather. No machine on earth can touch it.

Recommended Viewing:

- Armitage Leather — Saddle Stitch in Detail: A masterclass from one of Britain’s foremost saddlery educators, demonstrating the traditional awl-and-iron method. https://youtu.be/TGuiha5S2oE

- Armitage Leather — Saddle Stitching Technique (Extended): A deeper examination of needle coordination and tension control. https://youtu.be/7ue3zBg0bdA

- Hermès — Hearts and Crafts (Trailer): A rare glimpse inside the ateliers of the world’s most celebrated practitioner of hand-stitched luxury leather goods. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g6HOhqaVXW0

- Vogue — How Hermès Bags Are Made: An unprecedented behind-the-scenes tour of the Hermès leather goods studio, featuring artisans demonstrating traditional saddle stitching on Birkin and Kelly bags. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7LJrU4443Q