A Guide to USDA Beef Grades

You’re standing at the butcher counter, staring at three ribeye steaks that look almost identical—yet one costs $13 a pound, another $18, and the third $25. The difference? A small shield-shaped stamp and a single word: Prime, Choice, or Select. These USDA quality grades have shaped the American beef industry for nearly a century, yet most consumers have only a vague idea of what they actually mean. Understanding them can save you money, improve your cooking, and help you eat smarter.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s beef grading system is, at its core, a prediction of eating pleasure. It estimates how tender, juicy, and flavorful a cut will be based on two measurable traits: the amount of intramuscular fat (known as marbling) and the physiological maturity of the animal at slaughter. According to the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, the agency employs roughly 200 highly trained graders who evaluate beef carcasses across the country, often with the aid of electronic imaging instruments (USDA – Beef Up Your Knowledge: Marbling 101).

A 2015 study by Dr. Daryl Tatum of Colorado State University found that steaks graded USDA Prime delivered a positive eating experience 97% of the time, compared to 82% for Low Choice and just 66% for Select (South Dakota State University Extension). Those numbers tell a compelling story: the grade on the label really does matter. But the full picture is more nuanced—and far more interesting—than most shoppers realize.

In this guide, we’ll trace the history of beef grading from its wartime origins to modern genetic science, decode what each grade actually measures, and arm you with the knowledge to make confident choices the next time you’re staring down that meat case.

From Wartime Rations to Your Weekend Grill: A Century of Beef Grading

The story of USDA beef grading begins not at a steakhouse, but on a battlefield. In 1916, the USDA drafted its first tentative standards for beef carcass grades to help standardize meat procurement for the U.S. Armed Forces during World War I. The military needed a common language for buying beef in enormous quantities, and those early standards provided it (Texas A&M Meat Science – History of Meat Grading).

After the war, the system gained broader commercial appeal. Hospitals, railroads, hotel dining cars, and large retailers all wanted uniform purchasing standards. In May 1927, the USDA launched a one-year national experimental program of voluntary beef grading and stamping. A coalition of ranchers called the Better Beef Association championed the trial, believing that quality designations would boost demand for well-marbled, corn-fed cattle during an agricultural recession. They were right. Grading allowed smaller processing plants to compete with industrial giants by proving their product was just as good—or better.

Initially, grading was free. Twelve months later it moved to a fee-for-service model, and it has remained voluntary ever since. During World War II, grading temporarily became mandatory as part of wartime price controls under the Office of Price Administration.

The original grade names were Prime, Choice, Good, Medium, Common, Cutter, and Canner. In 1949, the USDA shuffled the deck: “Select” became “Choice,” and “Choice” was elevated to “Prime.” In 1987, the name “Good” was changed to “Select”—a rebranding designed to make leaner beef sound more appealing at a time when Americans were turning away from dietary fat. Major revisions also occurred in 1965, 1975, and 1997, each time recalibrating the marbling thresholds in response to evolving science, consumer preferences, and industry economics (Flannery Beef – USDA Grading Scale).

Fun fact: The concept of “marbling” was originally quantified by boiling meat samples and weighing the extracted fat. Today’s graders achieve comparable accuracy using visual assessment and digital camera technology in a matter of seconds.

Watch: The USDA collaborated with the U.S. Meat Export Federation and Colorado State University to produce a comprehensive overview of the beef grading process: USDA Beef Grading – Farm to Table (YouTube)

Behind the Stamp: How a USDA Grader Evaluates Your Steak

Beef grading takes place at the packing plant after slaughter but before the carcass is broken down into retail cuts. Here’s what happens:

Step 1 – Ribbing the Carcass. A trained USDA grader, employed by the Agricultural Marketing Service (not the packing company), makes a precise cut between the 12th and 13th ribs of each carcass. This exposes the ribeye muscle—the longissimus dorsi—which is the only muscle evaluated for quality grade under the U.S. system (USDA AMS – Carcass Beef Grades and Standards).

Step 2 – Evaluating Maturity. The grader assesses the physiological age of the animal by examining skeletal ossification (how much cartilage has turned to bone in the vertebrae), the shape and color of the ribs, and the color and texture of the lean muscle. Younger animals—classified as “A maturity” (roughly 9–30 months old)—produce more tender beef because their collagen, the connective tissue protein that gives meat structure, has undergone less cross-linking. As South Dakota State University Extension explains, collagen cross-linking makes muscle progressively tougher with age, which is why maturity matters almost as much as marbling.

Step 3 – Scoring Marbling. The grader evaluates the amount, size, and distribution of white fat flecks within the ribeye’s lean tissue. Marbling is described on a 10-point scale ranging from “Practically Devoid” at the bottom to “Very Abundant” at the top, with each level subdivided into 100 sub-scores. Modern graders are often aided by digital camera systems that produce heat-map images of intramuscular fat, reducing human variability (USDA – Understanding Meat Grading).

Step 4 – Assigning the Grade. The grader plots the intersection of maturity and marbling on the official USDA quality grading chart. A carcass with A maturity and “Slightly Abundant” or higher marbling earns Prime. The same maturity with “Small” to “Moderate” marbling earns Choice. “Slight” marbling yields Select. Below that, the meat falls into Standard, Commercial, Utility, Cutter, or Canner—grades that consumers rarely see in a retail setting.

It’s important to note that grading is entirely voluntary. Packers request and pay for the service. Not every carcass is graded—ungraded beef is often sold as “store brand” or “no-roll” meat. The USDA also assigns a separate yield grade (1 through 5) that estimates the amount of usable lean meat on the carcass, but consumers rarely encounter yield grades at retail.

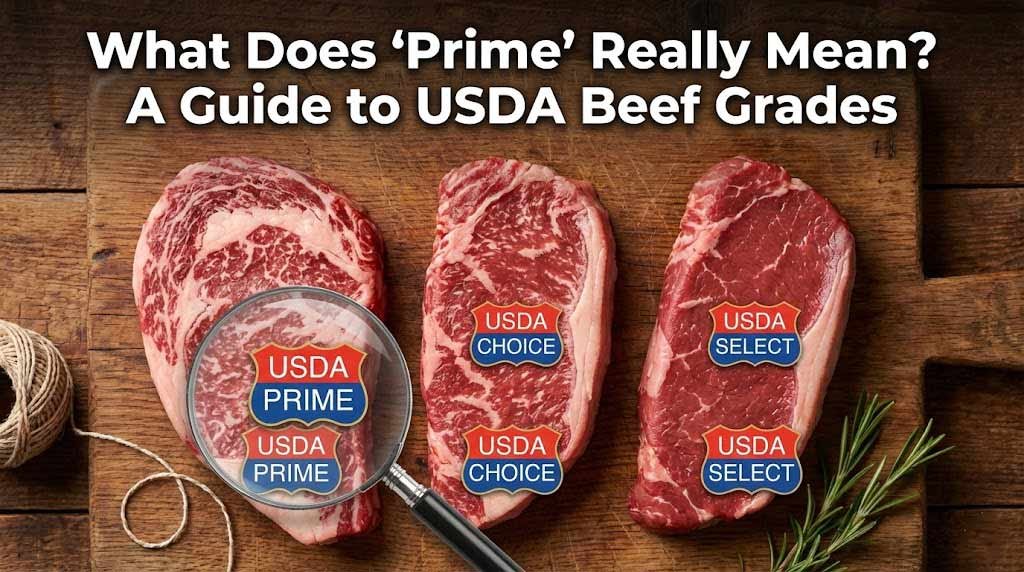

The Big Three: Prime, Choice, and Select Decoded

While the USDA recognizes eight quality grades, only three matter at the grocery store and restaurant level. Here’s what separates them:

USDA Prime

Prime sits at the top of the pyramid. It requires abundant marbling—roughly 8–13% intramuscular fat—and must come from young cattle in the A or B maturity range (generally under 42 months old). The dense web of fat within the muscle melts during cooking, basting the meat from the inside and producing extraordinary tenderness and rich, buttery flavor. Prime is ideal for high-heat, dry cooking methods: grilling, broiling, roasting, and sous vide. According to Ray Riley of the Texas A&M Rosenthal Meat Science and Technology Center, “Prime provides a higher probability of getting a quality cut overall” (Texas A&M AgriLife – Beef Grades 101).

USDA Choice

Choice beef features moderate marbling—about 4–10% intramuscular fat. Within the Choice grade, there are three sub-tiers based on marbling score: Moderate (high Choice, sometimes called “Premium Choice”), Modest (mid-Choice), and Small (low Choice). This variation means that top-tier Choice can rival low-end Prime, while bottom-tier Choice may barely outperform Select. Choice is the workhorse of the American beef market and the grade most commonly found in grocery stores and casual dining restaurants. Loin and rib cuts graded Choice are excellent for grilling; less tender cuts benefit from braising or slow-cooking.

USDA Select

Select beef is leaner, with only about 2–4% intramuscular fat and “Slight” marbling. It’s uniform in quality and budget-friendly, but it lacks the juiciness and depth of flavor found in higher grades. Select cuts perform best when marinated before grilling or cooked low-and-slow through braising, stewing, or smoking to compensate for the lower fat content.

Quick Comparison at a Glance

• Prime: 8–13% fat | Abundant marbling | ~10–12% of graded beef | $18–$30+/lb for steaks

• Choice: 4–10% fat | Moderate marbling | ~72–75% of graded beef | $13–$20/lb for steaks

• Select: 2–4% fat | Slight marbling | ~13–14% of graded beef | $9–$15/lb for steaks

Note: Prices vary widely by region, cut, and retailer. These ranges are general estimates as of 2025.

The Numbers Are Shifting: How Genetics and Feed Are Rewriting Beef Quality

For decades, the conventional wisdom was that only about 2–3% of American beef earned the Prime designation. That number has changed dramatically. According to USDA grading data, approximately 10.5% of fed cattle carcasses graded Prime in 2024—more than double the percentage from just ten years earlier. Prime carcass production reached a record 2.55 million head that year (Certified Angus Beef – Prime Trends Up). By mid-2025, the Prime share had climbed to an average of 11.5% of fed cattle, defying seasonal expectations.

The same upward trajectory applies to Choice. University of Tennessee data shows that the average annual percentage of beef grading Choice or higher rose from 62% during 2000–2010 to about 85% during 2020–2024. By the first half of 2025, nearly 87% of all graded beef hit Choice or better (UT Beef & Forage Center – Changes in Beef Quality Grade). Meanwhile, Select’s share has plummeted from roughly 35% in the early 2000s to under 14% today.

What’s driving this seismic shift? Agricultural economists Josh Maples of Mississippi State University and James Mitchell of the University of Arkansas point to three factors:

1. Genetic Improvement. Decades of selective breeding have produced cattle with greater marbling potential. Angus-influenced genetics, in particular, have been widely adopted across commercial herds for their consistent ability to grade well.

2. Feedlot Management and Longer Days on Feed. Modern feedlots can fine-tune nutrition to optimize intramuscular fat deposition. During and after COVID-19, the industry trended toward keeping cattle on feed longer, which increases marbling. In 2024, the average fed steer carcass weighed 931 pounds—124 pounds heavier than in 2004 (Beef Magazine – Percentage of Choice-Graded Beef Grows).

3. Economic Incentives. Packer grid pricing rewards higher-grading cattle with premium payments. Some focused breeders now achieve upward of 50% Prime carcasses through targeted genetics, making Prime a realistic economic goal rather than a rare outluck.

The practical result? Prime beef is more available to everyday consumers than ever before. Once reserved almost exclusively for high-end restaurants, Prime cuts are now regularly stocked at Costco, Whole Foods, and other major retailers. As the Certified Angus Beef brand notes, the retail grocery sector “woke up to the fact that Prime beef cuts could be accessed dependably throughout the year,” unlocking consumer demand where it hadn’t been tapped before.

Beyond the Grade: Wagyu, Certified Angus, and What the Label Doesn’t Tell You

USDA grades are a powerful tool, but they don’t capture everything that affects how beef tastes on your plate. Several factors fall outside the grading system’s scope:

Breed. Not all Prime beef is created equal. A Prime-graded Angus steak and a Prime-graded Holstein steak may have the same marbling score but differ significantly in flavor, texture, and fat composition. Japanese Wagyu cattle, renowned for their extraordinary marbling, are graded on a separate Beef Marbling Scale (BMS) of 1 to 12. Because the USDA scale tops out at “Very Abundant,” many Wagyu cuts that would rate BMS 8, 9, or even 12 in Japan receive the same “Prime” stamp as conventionally raised American beef—despite being in an entirely different class of quality (Carnez Meats – USDA Grading Explained).

Certified Programs. Branded beef programs layer additional specifications on top of USDA grades. The Certified Angus Beef® (CAB) brand, for example, requires 10 quality specifications beyond the base USDA grade, including moderate-or-higher marbling, specific carcass size parameters, and Angus-type phenotype. About 90% of eligible cattle that fail CAB certification fall short on marbling requirements. Only the upper two-thirds of Choice Angus carcasses may qualify, making CAB a reliable indicator of above-average eating quality within the Choice grade.

Grass-Fed vs. Grain-Finished. USDA grades place heavy emphasis on marbling, and marbling is largely a product of grain finishing. Grass-finished beef is naturally leaner, which means it rarely grades above Select or low Choice. This doesn’t mean grass-fed beef is inferior—many consumers prefer its distinct, mineral-rich flavor profile—but it does mean the grading system was not designed to evaluate its strengths. As Ray Riley of Texas A&M warns, “Don’t let the connotation of wagyu beef throw you off…its ability to marble doesn’t mean it may not have the same amount of marbling or lack thereof as Select at times.” The same caveat applies to grass-fed labels.

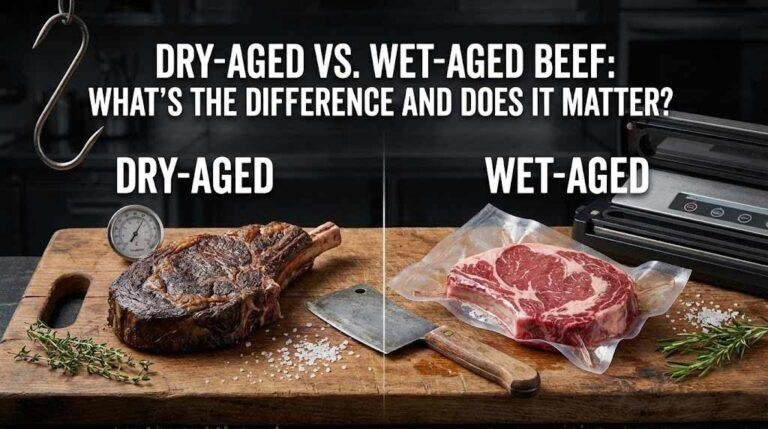

Aging and Cooking Method. A properly dry-aged Choice steak can rival or exceed a fresh Prime steak in tenderness and flavor complexity. Cooking method matters enormously, too: a beautifully marbled Prime ribeye cooked to well-done will be less enjoyable than a carefully reverse-seared Choice cut brought to a perfect medium-rare. Grade sets the ceiling; technique determines how close you get to it.

Watch: For a deep dive into the science of beef quality and marbling, check out the American Meat Science Association’s detailed explainer: The Science Behind the Grade (USDA AMS)

Shopping Smart: A Practical Guide to Buying Beef by Grade

Armed with knowledge of the grading system, you can shop strategically rather than reflexively reaching for the most expensive option. Here’s a framework for matching grade to occasion and cooking method:

When to Buy Prime

Splurge on Prime for special occasions when the steak is the star—birthdays, anniversaries, holiday dinners. Prime shines with minimal seasoning and simple, high-heat methods: a seared ribeye, a slow-roasted prime rib, a grilled porterhouse. The abundant marbling provides built-in insurance against overcooking, making Prime a forgiving choice for less experienced grill-masters. Look for Prime at warehouse clubs like Costco, specialty butchers, and online purveyors like Snake River Farms or Chicago Steak Company.

When to Buy Choice

Choice is the everyday champion. For weeknight grilling, backyard barbecues, and most restaurant-quality meals at home, a good Choice steak delivers 90% of the Prime experience at 60–70% of the price. Pro tip: Look for Choice cuts with visible marbling that approaches the higher end of the spectrum—sometimes labeled “Upper Choice” or “Premium Choice.” These represent exceptional value. Choice is also the ideal grade for brisket, chuck roasts, and other cuts destined for the smoker or slow cooker, where extended cooking renders fat beautifully.

When to Buy Select

Select is a smart pick when the beef won’t be the flavor centerpiece. Think stir-fries, fajitas, stews, chili, or any recipe with bold marinades and sauces that compensate for lower fat content. Select is also a reasonable choice for health-conscious eaters watching their saturated fat intake. Just avoid dry-heat grilling a Select steak without a marinade—you’ll likely end up with a tough, dry result.

Reading the Meat Case Like a Pro

Look for the USDA shield stamp on the packaging—it’s your assurance that the grade was assigned by a federal grader, not the store’s marketing department. Be wary of proprietary labels like “Premium,” “Reserve,” or “Gold Label” without a USDA grade—these have no official definition and may mask lower-quality meat. When a USDA grade isn’t displayed, use your eyes: look for fine, evenly distributed white flecks of fat throughout the lean muscle. Avoid cuts where the fat appears only as a thick exterior cap with little internal marbling.

According to USDA retail data, Choice steaks like New York Strip or Top Sirloin typically cost $2–$4 per pound more than Select equivalents. The premium from Choice to Prime varies more widely but can range from $5–$12 per pound depending on the cut and retailer (SDSU Extension – USDA Beef Quality Grades).

The Future of Beef Grading: Technology, Sustainability, and Changing Palates

The USDA grading system has endured for nearly a century, but it’s not standing still. Several forces are reshaping how Americans evaluate and value beef quality:

Camera Grading and AI. In 2024, the USDA introduced updated marbling grading cards and continued expanding the use of camera-based grading systems. These digital tools capture high-resolution images of the ribeye and algorithmically score marbling with greater consistency than the human eye alone. As adoption grows, expect more standardized and arguably fairer grading outcomes across the industry (Chowhound – Why Only 10% Gets Prime).

The Grass-Fed Question. Consumer demand for grass-fed and organic beef continues to grow, driven by health preferences and sustainability concerns. But because the USDA grading system was built around grain-finished marbling, grass-fed beef is structurally disadvantaged. Some industry observers argue that a parallel grading framework—one that evaluates flavor complexity, omega-3 content, or environmental footprint alongside marbling—could better serve a diversifying marketplace.

Sustainability Tensions. Prime beef requires extended grain finishing, which carries a larger carbon and water footprint than leaner production systems. As climate-conscious consumers increasingly scrutinize the environmental cost of their food choices, the industry faces a tension between producing higher-marbled beef (which commands premium prices) and reducing its ecological impact. Regenerative ranching programs and carbon-offset initiatives represent early efforts to reconcile these competing priorities.

The Ceiling Question. With 87% of graded beef already hitting Choice or higher, economists wonder how much further quality percentages can climb. Moving from 85% to 90% Choice-or-better “will be much more difficult than moving from 62% to 85%,” notes the University of Tennessee’s Beef & Forage Center. Genetic and nutritional gains face diminishing returns, meaning the industry may be approaching a natural plateau.

Global Context. While the U.S. system focuses on marbling and maturity, other countries grade differently. Japan rates beef on a BMS scale of 1–12 for marbling plus separate scores for meat color, firmness, and fat color. Australia uses both AUS-MEAT and Meat Standards Australia systems with marbling scales up to 9. The EU’s EUROP grid emphasizes carcass shape and fat covering over marbling entirely. As global beef trade expands, consumers benefit from understanding that “quality” is defined differently depending on which side of the ocean you’re standing on.

The Grade Is the Beginning, Not the End

The USDA beef grading system is one of the great standardization success stories in American food. Born from the logistical demands of wartime and refined through a century of science, economics, and consumer feedback, it provides a remarkably reliable shorthand for eating quality. A Prime steak really is more likely to deliver a memorable meal than a Select cut—the data proves it.

But a grade is a starting point, not a guarantee. The breed of cattle, the specifics of its diet, how the beef was aged, and—most critically—how you cook it all shape the final experience on your plate. A skillfully prepared Choice brisket from a dedicated pitmaster will outshine a poorly handled Prime filet every time.

The smartest approach? Know what the grades mean, match them to your cooking method and occasion, and let your eyes and instincts do the final selection at the meat case. Whether you’re firing up the grill for a Tuesday night dinner or planning an elaborate holiday feast, understanding what “Prime” really means puts you in control of both quality and value.

Happy grilling.

Sources & Further Reading

• USDA – What’s Your Beef – Prime, Choice or Select?

• USDA AMS – Beef Grading Shields and Marbling Pictures

• Texas A&M Meat Science – History of Meat Grading in the United States

• South Dakota State University Extension – USDA Beef Quality Grades: What Do They Mean?

• Tatum, D. (2015). Recent Trends: Beef Quality, Value and Price. Colorado State University.

• Certified Angus Beef – Prime Trends Up (February 2025)

• University of Tennessee – Cattle Economics: Changes in Beef Quality Grade

• Beef Magazine – Percentage of Choice-Graded Beef Grows (May 2025)

• Drovers – Improving the Grade: More Than 10% of Carcasses Grading Prime

• USDA National Steer & Heifer Grading Report – NW_LS196 (December 2024)

Video Resources• USDA Beef Grading: Farm to Table (YouTube) – Official USDA/Colorado State University overview of the complete grading process.