There is a particular sound that haunts every leather craftsman who has spent decades with an awl in his hand and oak-bark tannin under his fingernails. It is the dull, fibrous thud of a blade cutting through what should be full-grain cowhide but instead reveals compressed fiberboard, foam sheeting, and polyurethane coating masquerading as structure. I have heard this sound more times than I care to remember—on my workbench in Huntington, at trade shows in Manhattan, and once, memorably, when a Manhattan litigator brought me a $600 “Italian leather” attaché whose handle had torn clean off its body after nine months of daily commuting, exposing a cardboard stiffener so thin it could have passed for a cereal box panel. That moment crystallized something I had known instinctively since I began building briefcases in 1995: the modern leather goods industry has perfected the architecture of illusion, and the professionals who trust these objects with their livelihoods deserve to understand what is actually holding their briefs, their laptops, and their reputations together.

The global luxury leather goods market generated an estimated $66 billion in revenue in 2025, with the United States alone accounting for roughly $13 billion of that figure (Statista Market Forecast, 2024). Demand for handcrafted leather goods has surged by approximately 26 percent since 2022 (Market Growth Reports, 2024). Yet CBS News reported that some major conglomerates were selling handbags marked up as much as twenty times their production cost, and that bags costing under $100 to manufacture were appearing on retail floors at $1,200 (CBS News, 2016). The implications for briefcases—objects that professionals carry into courtrooms, boardrooms, and operating theaters—are staggering. If the disparity between perception and reality is this severe in handbags, what is happening inside the briefcase your career depends on?

This is not a question of brand snobbery. It is a question of engineering. And it is a question I have spent thirty years answering, one saddle stitch at a time.

The Anatomy of a Shortcut: What Is Actually Inside a Mid-Range Briefcase

The modern mid-range briefcase—let us define that as the $300 to $700 range occupying the shelves of department stores and the pages of Amazon—has been engineered not for longevity but for the appearance of longevity at the moment of purchase. The exterior may be labeled “genuine leather,” but that designation occupies the lowest rung of the leather quality hierarchy, sitting just above bonded leather, which leather experts have compared to the particleboard of the leather world (Popov Leather, 2025). Manufacturers take lower layers of the split hide, coat them with polyurethane or vinyl, and emboss an artificial grain pattern to simulate the texture of full-grain material (Buffalo Jackson, 2020).

Inside, the construction story grows darker. Where a traditionally built briefcase relies on the inherent rigidity of thick vegetable-tanned leather—typically 1.4 to 1.8 millimeters for full-grain material—to maintain its form, mass-produced alternatives substitute structural integrity with stiffening agents: compressed cardboard panels, non-woven fiberboard, foam laminates, and synthetic reinforcements glued between layers of thin leather or fabric (The Bag Making Suppliers, 2025). These materials do precisely what they are designed to do—hold shape on a showroom shelf and through the first ninety days of ownership. But they were never designed to endure the sustained compression of a daily commute, the humidity of a subway platform in August, or the cyclical stress of a briefcase being opened and closed forty times a week for a decade.

Think of it this way. In my other life at The Heritage Diner, I have been seasoning the same cast-iron skillets for over two decades. Real cast iron gets better with every use, every layer of carbonized oil deepening its non-stick surface. But the bargain-bin skillets coated with a thin veneer of non-stick spray? They flake, they warp, they end up in landfills within two years. The $500 briefcase with cardboard stiffeners is the non-stick skillet of the professional accessories world. It performs adequately until the moment it does not—and that moment always arrives.

The Leather Hierarchy: A Field Guide for Professionals

Understanding why your briefcase disappoints begins with understanding what “leather” actually means in the context of modern manufacturing. The industry recognizes a clear hierarchy, and knowing it is the single most important tool you can carry into a purchase decision.

Full-grain leather sits at the apex. This is the complete outer surface of the hide with all natural markings intact—scars, insect bites, stretch marks, the biographical record of a living animal. It is the strongest, most durable grade, and it develops what leatherworkers call patina: a lustrous, deepening character that emerges through years of handling, sunlight, and the natural oils of human skin (Galen Leather, 2025). Full-grain leather does not need synthetic stiffeners because it possesses inherent structural memory. A briefcase made from proper full-grain vegetable-tanned leather at 1.4 millimeters or above will hold its form for decades.

Top-grain leather is the second tier—the outer layer sanded to remove surface imperfections, then stamped with an artificial grain. It sacrifices some durability and patina development for a uniform appearance.

Corrected-grain and “genuine” leather occupy a misleading middle ground. Despite the reassuring language, industry experts note that products labeled simply “genuine leather” are often manufactured from the lowest quality layers of the hide, heavily processed and containing none of the original natural grain (Galen Leather, 2025). Ironically, the word “genuine” has become a signal of compromise, not authenticity.

Bonded leather sits at the bottom—ground-up leather scraps mixed with polyurethane or latex binders and pressed onto a fiber sheet. One prominent leather retailer has described bonded leather as an amalgam of leather dust, vinyl, scraps, plastic, and glue (Mission Mercantile, 2023). It is the material equivalent of a pressed-wood desk stamped with a “mahogany” grain. No briefcase built from bonded leather should be expected to survive meaningful professional use.

The critical insight here is that your $500 briefcase very likely uses corrected-grain or genuine leather at best—materials that require synthetic stiffening to hold shape because the leather itself cannot do the job. The stiffener becomes structural, the leather becomes decorative, and you are paying for a costume.

English Bridle Leather: The Standard That Refuses to Compromise

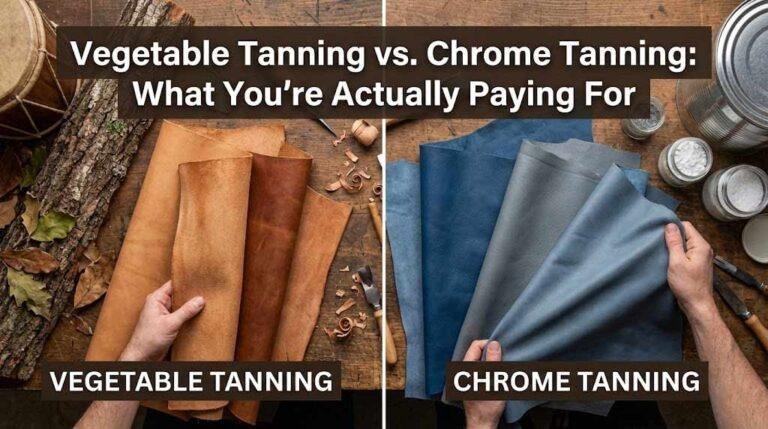

There is a reason I build Marcellino NY briefcases exclusively from English bridle leather, and it is not romanticism—it is engineering. English bridle leather is vegetable-tanned cowhide that undergoes an additional finishing process in which the hide is hot-stuffed with waxes and tallows before dye is applied, producing a material with a subtle matte sheen, exceptional rigidity, and profound resilience (Buckleguy, 2023). The tanning process itself, as practiced by heritage tanneries like Wickett & Craig in Pennsylvania and Sedgwick in England, takes approximately six weeks of soaking hides in solutions of mimosa and quebracho bark—a timeline that dwarfs the single day required for chrome tanning, which accounts for roughly 90 percent of global leather production (Wickett & Craig, 2025).

The vegetable tanning process fills the leather’s pores with natural wood fibers, producing a material that is stiffer, more structured, and more capable of holding form under stress than any chrome-tanned alternative (Saddleback Leather, 2025). When I cut a panel of English bridle for a Wallace or Habermas briefcase, I am working with a material that has been tanned pressure-tested at extraordinary levels of tensile strength. This leather does not need cardboard. It does not need foam. It does not need the architectural scaffolding that holds lesser briefcases together. The structure is the leather.

That is why, historically, English bridle leather was the material of choice for military ammunition pouches in nineteenth-century Western armies—applications where failure was not a matter of embarrassment but of survival (LeFren Leather, 2025). When briefcase makers in London and New York adopted bridle leather for professional cases in the early twentieth century, they were applying a military-grade material to civilian use. That tradition is what I carry forward in my workshop, hand-saddle-stitching each Marcellino piece using methods unchanged from how these cases were built over a century ago.

The Five-Point Inspection: How to Expose a Briefcase’s True Construction

You do not need thirty years of leatherworking experience to assess the structural honesty of a briefcase. You need your hands, your nose, and five minutes of careful attention.

Press the panels. Place your palm flat against the side of the briefcase and press inward. Full-grain vegetable-tanned leather will yield with a controlled flex—the dense fiber network compresses and springs back, much like pressing the pad of your thumb. Cardboard-stiffened panels feel rigid at first but lack resilience; they compress flatly and may produce a faint crinkling sensation. If the panel feels like pressing on a manila folder sandwiched between fabric, you are feeling the stiffener, not the leather.

Examine the edges. In a properly constructed leather briefcase, the edges are burnished—sanded, dyed, and sealed in multiple layers over a period of hours. This is how I finish every edge on a Marcellino piece, building up a smooth, glass-like profile that seals the raw leather against moisture and wear. Mass-produced alternatives fold the leather over the edge and glue it down, or apply a single coat of edge paint that begins peeling within months. If you see a uniform, plastic-looking ridge along the edges, you are looking at cost-cutting, not craftsmanship.

Smell the material. Genuine vegetable-tanned leather has a distinctive earthy, woody aroma—the olfactory signature of tannins from oak, chestnut, and mimosa bark. Chrome-tanned leather smells faintly chemical. Corrected-grain and bonded leathers often carry a pronounced plastic or chemical odor from their polyurethane coatings. As leather expert Volkan Yilmaz has noted in his widely followed deconstruction analyses, a brief, natural, earthy aroma is one of the most reliable indicators of properly tanned material (Dazed Digital, 2023).

Inspect the grain. Run your fingertips across the surface. Natural full-grain leather displays subtle variations—pore density shifts, faint scars, and slight textural differences from one area to another. These are not defects; they are proof of biological origin. If the grain pattern repeats with mechanical regularity, you are looking at an embossed corrected-grain surface, an artificial texture stamped onto inferior material to simulate natural character.

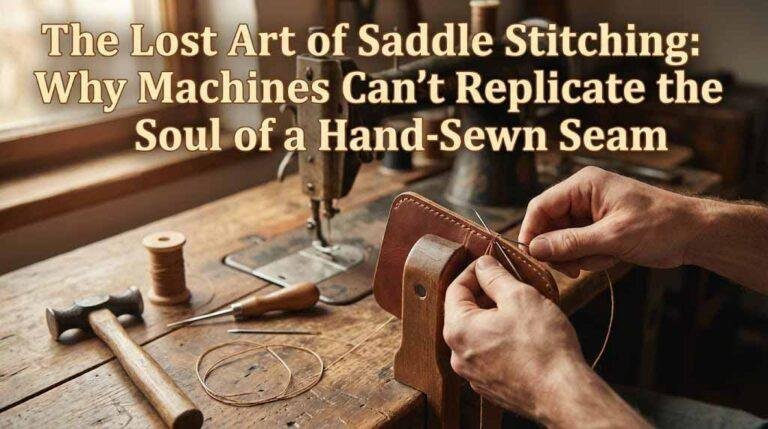

Ask about the stitching. Machine stitching uses a lock stitch that, when a single thread breaks, unravels in both directions. Hand-saddle stitching—the method I use on every Marcellino briefcase—uses two needles passing through the same holes in opposite directions, creating independent loops. When a thread breaks in a saddle stitch, the adjacent stitches hold. It is the difference between a zipper and a stone wall. If the manufacturer cannot tell you what stitch method they use, that answer is, in itself, the answer.

The Economics of Deception: Why the Industry Builds This Way

The luxury goods sector has not embraced shortcuts out of malice. It has embraced them out of mathematics. The Business of Fashion and The New York Times have reported that the average cost of manufacturing and selling a luxury bag is approximately 35 percent of its final retail price, with high-quality leather and materials constituting roughly 30 percent of total production cost and labor accounting for about 40 percent (PurseBlog, 2013; The School of Luxury Retail, 2025). Fashion startup Oliver Cabell revealed that bags they produced for $285—including $71.57 in materials, $69.95 in labor, and $8.92 in tax—were functionally equivalent to products retailing for over $1,600 from established French luxury houses (FashionBeans, 2021).

Those economics create a specific incentive structure. Every dollar saved on materials—substituting corrected-grain for full-grain, replacing leather structure with fiberboard stiffeners, switching from hand-saddle stitching to machine lock stitch—flows directly to margin. The consumer cannot see the substitution at point of sale. The showroom lighting flatters the embossed surface. The new-product stiffness mimics genuine structural integrity. The cardboard does not reveal itself until the sixth month, the eighth month, the moment the bottom panel sags under the weight of a fifteen-inch laptop and two legal pads.

This is what I call the “gentrification of quality”—a term I have been using in conversations about Mount Sinai and the broader North Shore for years, as Paola and I prepare to open our boutique in 2026. Just as rising property values can displace authenticity from a neighborhood, rising margins can displace genuine materials from a product category. The word “luxury” gets applied to progressively less luxurious objects until it means nothing at all. On the North Shore, we fight that drift by investing in real community—the Heritage Diner has been a Mount Sinai institution for over two decades because the sourdough is made from scratch and the cast iron never sees a shortcut. In leatherwork, I fight that drift by refusing to put my name on anything that needs a cardboard skeleton to stand upright.

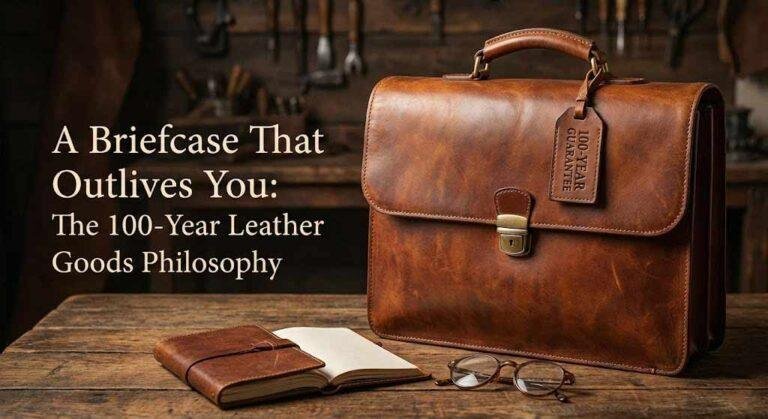

The Patina of Time: Why Investing in Real Construction Pays Dividends

Martin Heidegger wrote about the concept of Zuhandenheit—readiness-to-hand—the quality of a tool so well-suited to its purpose that it becomes an extension of the person who uses it, disappearing into the act of use. A briefcase built from proper materials achieves this state. After six months of daily carry, the English bridle leather begins to soften at the points of contact—the handle, the flap fold, the corners that brush against a hip or a car seat. The surface oils emerge, producing a lustrous depth that raw leather cannot possess. After two years, the briefcase has become biographical, recording the rhythms and routines of its owner in the language of patina. After a decade, it is an heirloom.

A cardboard-stiffened briefcase achieves something else entirely. After six months, the edges begin to fray where the thin leather separates from the adhesive. After a year, the bottom panel dimples permanently from repeated weight bearing. After two years, the synthetic stiffeners—which absorb moisture but cannot release it—begin to warp, pulling the leather into unintended shapes. The briefcase does not age; it deteriorates.

This distinction maps perfectly onto what I have observed in the real estate market across Mount Sinai and the greater North Shore. There are houses built with real materials—solid oak framing, hand-laid stone, copper flashing—that appreciate in character and value with every passing decade. And there are houses built with the architectural equivalent of corrected-grain leather: vinyl siding over oriented strand board, staged to look magnificent on listing day and sagging by year five. Paola sees this every day in her work as a broker. The most durable investments, in real estate as in leather, are the ones where the structure is the value—not a veneer applied over compromise.

The arithmetic of longevity confirms this. A mass-produced briefcase at $500, replaced every two to three years, costs $2,000 to $2,500 over a decade. A Marcellino Habermas in English bridle leather at $2,800 to $3,000 lasts fifteen to twenty years or more, developing only deeper character with time. The cost-per-year of the bespoke piece is lower. The cost-per-impression—every meeting, every courtroom appearance, every client handshake in the presence of that briefcase—is incalculably lower. You cannot put a number on the moment a colleague reaches over and touches the leather and says, What is this?

That question is the patina of time speaking. And cardboard never learns to speak.

Further Reading: Wickett & Craig’s vegetable tanning process—the Pennsylvania tannery, operating since 1867, whose English bridle leather I use in every Marcellino briefcase: wickett-craig.com/vegetable-tanning

Further Reading: Popov Leather’s comprehensive leather quality chart—an accessible guide to the full-grain, top-grain, genuine, and bonded leather hierarchy every consumer should understand: popovleather.com/leather-grades

Further Reading: The full Marcellino NY collection of hand-saddle-stitched English bridle leather briefcases, built one at a time in the tradition outlined in this article: marcellinony.com

Peter Joseph is the founder of Marcellino NY, a bespoke English bridle leather briefcase atelier serving lawyers, physicians, and collectors worldwide since 1995. He is also the proprietor of The Heritage Diner in Mount Sinai, New York—a twenty-five-year neighborhood institution—and is preparing to launch a boutique retail experience on the North Shore in 2026 with his wife, Broker Paola. He can be reached at jp@marcellinony.com.