There is a moment, somewhere around the fourteenth month, when a hide that has been resting in oak bark liquor at J. & F.J. Baker’s tannery in Devon, England, crosses a threshold that no laboratory instrument can adequately measure. The collagen fibers, having slowly surrendered their water molecules to tannins extracted from coppiced English oak, achieve a density and tensile integrity that will outlast the person who commissioned the leather. I have held that leather in my hands—cut it, stitched it, shaped it into briefcases that now travel between courtrooms in Manhattan and boardrooms in Dubai. And I can tell you, with the certainty of a man who has spent decades working with his hands while simultaneously running a quarter-century diner on the North Shore of Long Island, that the difference between vegetable-tanned and chrome-tanned leather is not a matter of opinion. It is a matter of chemistry, philosophy, and ultimately, what you believe about the relationship between time and value.

At the Marcellino NY workshop, we build every briefcase from full-grain English bridle leather that has been vegetable-tanned using methods that predate the Industrial Revolution. When clients ask why a Marcellino piece costs what it does, the answer begins not with craftsmanship—though that matters enormously—but with tanning. The process that transforms a raw animal hide into the material from which a legacy is built. Most consumers have never been asked to think about this. The luxury goods industry prefers it that way. But if you are spending real money on leather—whether it is a handbag, a pair of shoes, a belt, or a briefcase meant to accompany you through thirty years of professional life—you deserve to understand what is actually happening at the molecular level, and what those molecular decisions mean for your wallet, your ethics, and the thing you will carry every day.

The Molecular Divide: Collagen, Tannins, and the Architecture of Permanence

Every piece of leather begins as collagen—the structural protein that constitutes roughly 80 percent of animal skin. Collagen molecules naturally align into triple-helix structures that bundle together into visible fiber networks. Left untreated, these fibers are susceptible to hydrolysis: water breaks the chemical bonds, bacteria colonize the organic material, and the hide rots. Tanning is the intervention that arrests this decay. It replaces water molecules within the collagen matrix with stabilizing agents that prevent degradation while preserving flexibility (Carryology, 2024).

Here the roads diverge.

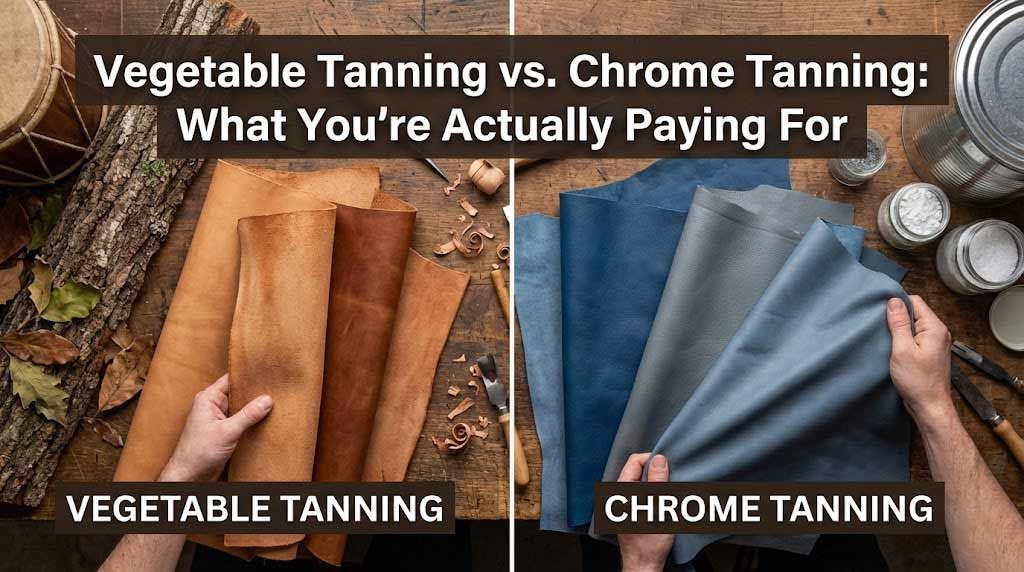

Vegetable tanning employs polyphenolic compounds—tannins—derived from the bark, leaves, and roots of trees such as oak, chestnut, mimosa, and quebracho. These large organic molecules bond with the collagen proteins through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, gradually displacing water and creating a dense, stable material. The process is achingly slow. At its most traditional, as practiced by Baker’s of Colyton—the last remaining oak bark tannery in Britain, operating on a site that has produced leather since Roman times—hides are suspended in a series of 72 tanning pits, moving from weaker to stronger concentrations of oak bark liquor over three months, then layered flat with handfuls of bark for an additional nine months (J. & F.J. Baker & Co., 2024). The total cycle: twelve to fourteen months of patient, unhurried transformation.

Chrome tanning, by contrast, uses chromium(III) sulfate salts—synthetic mineral compounds whose smaller molecular size allows rapid penetration into the collagen structure. The entire process can be automated and completed within twenty-four hours (Gentleman’s Gazette, 2020). Developed in 1858 as the leather industry raced to meet the appetites of the Industrial Revolution, chrome tanning now accounts for approximately 90 percent of global leather production (Heddels, 2025). The economic logic is irresistible: faster throughput, lower labor costs, greater uniformity.

But speed and economy are not the same as quality. And they are certainly not the same as permanence. I think about this every morning when I unlock the Heritage Diner at 5:30 a.m. and fire up cast-iron griddles that have been seasoned over twenty-five years of continuous use. You cannot rush a seasoned surface. You cannot accelerate the polymerization of oil into a nonstick patina through sheer force of will. Some things answer only to time—and leather is one of them.

The Patina Question: Why Vegetable-Tanned Leather Ages Like a Fine Instrument

In the world of bespoke leather goods, “patina” is not a marketing term. It is a physical phenomenon—and it is the single most consequential difference between these two tanning methods for anyone investing in a piece meant to endure.

Vegetable-tanned leather is inherently absorbent. The natural tannins leave the collagen fibers open to interaction with their environment: the oils from your hands, ambient light, temperature fluctuations, the particular chemistry of your daily routine. Over months and years, these interactions produce a deepening of color, a warming of tone, and a surface luster that is utterly unique to each piece. A Marcellino briefcase that has accompanied a trial lawyer through five years of daily use will look nothing like the same model carried by a cardiologist across the same period. Each develops its own autobiography in leather. Baker’s of Devon describes this quality as a “mellowness combined with strength” that emerges from the gentle, undisturbed curing process—a density and lightness that drum-tanned leathers, agitated like laundry in industrial machines, simply cannot achieve (Tim Hardy Bespoke, 2024).

Chrome-tanned leather resists this evolution. The chromium salt cross-links are more rigid and uniform, inhibiting the natural oxidation and oil absorption that drive patina development. The result is a material that looks essentially the same on day one as it does on day one thousand. For certain applications—automotive upholstery, garment leather, products where color consistency matters more than character—this is a feature, not a flaw. But for a briefcase, a wallet, a belt, or any object meant to become more beautiful through use, chrome tanning forecloses the possibility of a relationship between maker, material, and owner that unfolds across time.

This is not unlike what we observe at the Heritage Diner with our cast-iron cookware versus nonstick pans. The nonstick surface performs identically from first use to last—and then it fails, catastrophically, when the coating degrades. The cast iron, properly maintained, becomes more effective with every year of service. The parallel to tanning chemistry is not metaphorical. It is structural. Polymerized oil on iron, polymerized tannin in collagen: both are cases where slow, organic accumulation creates something that synthetic shortcuts cannot replicate.

The Environmental Ledger: Chromium, Waterways, and the True Cost of Cheap Leather

The environmental calculus of leather tanning is more nuanced than most advocacy literature suggests, but the broad strokes are damning for industrial chrome processing.

The trivalent chromium (Cr III) used in tanning is, in isolation, a relatively low-toxicity compound—it occurs naturally in food and is a recognized dietary trace element. The danger emerges in the waste stream. When chrome-tanned leather scraps are incinerated or exposed to prolonged heat and sunlight, trivalent chromium can oxidize into hexavalent chromium (Cr VI)—a confirmed human carcinogen that causes respiratory cancers, kidney damage, and severe dermal ulceration (Blacksmith Institute, 2011). The United Nations Industrial Development Organization has reported that even with advanced waste management technologies, the residual chromium load from tanning operations creates persistent difficulties for landfill management (UNIDO, 2010).

The scale of the problem is staggering. Research published in Scientific Reports found that producing one square meter of finished shoe leather consumes approximately 126 liters of water, 2.83 kilograms of chemicals, and emits 8.54 kilograms of CO2 equivalent, with the tanning and finishing phases bearing the heaviest environmental burden (Kılıç et al., as cited in Scientific Reports, 2025). Chrome-tanned leather shavings constitute roughly 75 percent of all solid waste generated in leather manufacturing, and because the chromium-collagen crosslinks resist biodegradation, these shavings pose landfill challenges comparable to plastic waste (China et al., Chemosphere, 2020). The World Bank has ranked the leather industry ninth globally for negative environmental impact (Crudu et al., 2010).

Vegetable tanning is not environmentally innocent—it requires substantially more water than chrome processing and generates effluent that demands treatment before discharge. But its tanning agents are derived from renewable, sustainably harvested plant materials. Its waste is biodegradable. And critically, it produces no heavy metal contamination. Baker’s tannery in Devon operates a carbon-neutral process: the tanning pits are agitated by a 400-year-old water wheel mechanism, the drying sheds are heated by a biomass boiler fueled by the tannery’s own waste, and the oak bark is harvested from coppiced woodlands on a 15-to-20-year rotation cycle that allows regeneration from the root stool (Choose Real Leather, 2023). This is not greenwashing. This is a closed-loop system that has been operating, with minor refinements, since the era of the Tudors.

When Paola and I discuss the real estate we are developing in Mount Sinai for our 2026 boutique launch, we talk constantly about “embedded value”—the invisible decisions behind a property that determine whether it will appreciate or depreciate over decades. Tanning is the embedded value of leather. The consumer never sees the tanning pits. But every molecule in the finished product carries the consequence of what happened there.

What You Sacrifice with Chrome: Structural Integrity, Aroma, and the Question of “Feel”

Beyond patina and environmental impact, vegetable-tanned and chrome-tanned leathers diverge in several tactile and structural dimensions that matter enormously to anyone who works with their hands—or who simply pays attention to the objects they use daily.

Thickness and structure: Vegetable tanning preserves the hide’s natural fiber density. The slow, gentle process—particularly pit tanning, where hides rest undisturbed rather than tumbling in industrial drums—maintains the collagen’s original alignment. The result is a leather that is firm, holds its shape, and can be carved, tooled, and molded with precision. Chrome tanning produces a thinner, softer, more pliable material because the small chromium ions penetrate and partially disrupt the fiber structure. This is why chrome-tanned leather dominates in garments and gloves, where drape and stretch are paramount. But for a structured briefcase designed to protect documents and a laptop while maintaining its silhouette over decades, that softness becomes a liability. A chrome-tanned bag will slouch. A vegetable-tanned bag will stand.

Aroma: Vegetable-tanned leather carries the unmistakable scent of its origins—a warm, woody, slightly sweet fragrance that varies depending on the tannin source. Oak bark imparts a different olfactory signature than chestnut or mimosa. Chrome-tanned leather, when it carries any scent at all, tends toward a faintly chemical or metallic note. At Marcellino NY, clients frequently remark that opening a new briefcase is a sensory experience—the aroma of English bridle leather is inseparable from the experience of quality. This is not accident. It is chemistry. The volatile organic compounds released by natural tannins are, literally, the smell of centuries of accumulated botanical knowledge.

Edge finishing: Any leatherworker will confirm that vegetable-tanned leather burnishes beautifully—the edges can be polished with friction and wax to a smooth, glassy finish that is integral to the material. Chrome-tanned leather edges typically require acrylic paint or chemical sealants, which inevitably crack, peel, and degrade over time. The difference is visible at arm’s length, and it tells you everything you need to know about the underlying material.

The Combination Tannage and the Myth of the “Best of Both Worlds”

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging that the chrome-versus-vegetable binary is overly simplified. The industry has developed combination tannages—most famously Horween Leather Company’s Chromexcel, produced in Chicago since 1913—that employ both chrome and vegetable agents in sequence. These hybrid leathers can exhibit some patina development while retaining the suppleness associated with chrome processing (Stridewise, 2025).

But combination tannage is, at best, a compromise. It is the culinary equivalent of a diner that puts truffle oil on a frozen pizza and calls it artisanal. At the Heritage Diner, I learned long ago that the best ingredients prepared with the simplest techniques will always outperform mediocre ingredients subjected to complexity. The same principle holds in leather. The finest vegetable-tanned hides—from Baker’s in Devon, from the Tuscan tanneries that the Vera Pelle Italiana Conciata Al Vegetale consortium oversees, from Wickett & Craig in Pennsylvania, from Hermann Oak in St. Louis—do not need chrome supplementation. Their quality is a direct consequence of patience, material integrity, and the accumulated expertise of master tanners whose knowledge has been handed down through generations.

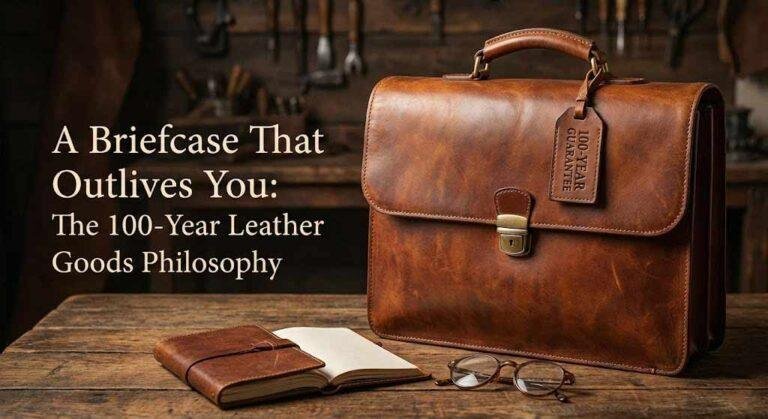

This is the Marcellino standard: we do not blend processes to save time. We do not compromise the tannage to reduce cost. Every briefcase is built from leather that has spent months, not hours, becoming what it is. Because a briefcase is not a disposable consumer good. It is a daily companion. And a companion should be worthy of the life it accompanies.

The Price Differential: Understanding What the Numbers Actually Represent

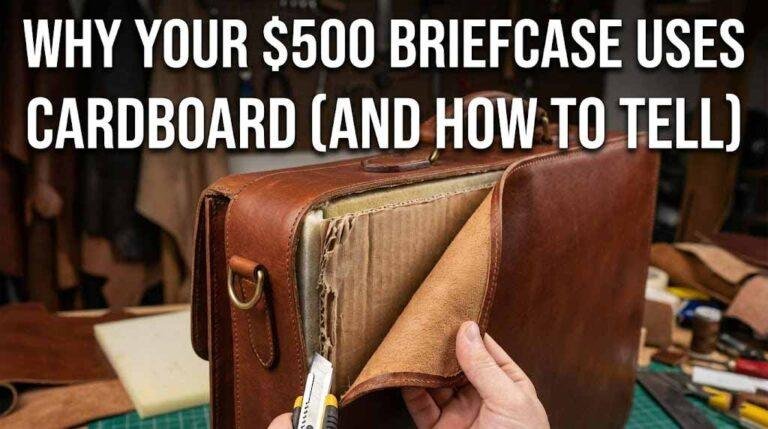

A full-grain vegetable-tanned briefcase from a serious maker will typically cost three to five times more than a comparable chrome-tanned product. The reasons are structural, not arbitrary.

Raw material cost: Vegetable-tanned hides from premium tanneries command significantly higher prices per square foot than chrome-tanned hides. Baker’s oak bark bridle leather, tanned over fourteen months using only water, oak bark, and the labor of master curriers, represents an extreme but illustrative case—the production capacity is limited to approximately 80 hides per week, each finished entirely by hand. Supply is inherently constrained by the physics of the process (J. & F.J. Baker & Co., 2024).

Waste factor: Vegetable-tanned leather’s natural variations—grain character, thickness inconsistencies, surface marks from the animal’s life—mean that a higher percentage of each hide is rejected or relegated to non-visible applications. Chrome-tanned leather’s uniformity reduces waste but achieves that uniformity through correction (sanding, embossing, pigment coating) that masks the hide’s authentic character.

Labor intensity: Hand-cutting, hand-stitching, and hand-finishing vegetable-tanned leather demands more skill and more time than working with the more forgiving chrome-tanned material. The leather itself dictates the pace.

Longevity value: Here is where the arithmetic reverses. A well-made vegetable-tanned leather briefcase, properly maintained, will serve its owner for twenty to thirty years—or longer. Its patina will deepen. Its structure will hold. Its edges will remain intact. A chrome-tanned equivalent, even from a reputable manufacturer, will begin to show material degradation within five to eight years: sagging, cracking at stress points, peeling at edges. Amortized over its functional lifespan, the vegetable-tanned piece is not more expensive. It is radically cheaper.

This is the same calculation that determines which properties appreciate in the North Shore luxury market—a subject Paola and I engage with daily as we prepare our 2026 Mount Sinai boutique venture. The houses built with honest materials and thoughtful craftsmanship hold their value. The ones built with shortcuts and clever staging do not. Leather is real estate for the body: the foundation matters more than the finish.

The Unseen Details: A Closing Reflection on the Ethics of Material Choice

Martin Heidegger wrote about the “thingness of things”—the idea that a well-made object possesses a quality of presence that extends beyond its function. A hand-forged tool, a stone wall laid without mortar, a hide tanned in oak bark for a year: these things carry within them the evidence of their making. They resist the anonymity of mass production. They insist on being encountered as particular, irreducible, real.

I think about this when I am at the Heritage Diner before dawn, preparing for a day that will involve hundreds of individual acts of care—cracking eggs onto a griddle whose seasoning represents a quarter century of accumulated attention, plating a dish whose presentation reflects a philosophy about how food should meet the eye before it meets the palate. I think about it when I am in the Marcellino workshop, drawing a needle through bridle leather whose every fiber was set in place by oak tannins over the course of a year in Devon. And I think about it when I stand in our Mount Sinai property, envisioning the boutique space where Paola and I will bring these worlds together in 2026—a space where craft, community, and commerce converge in a way that honors the unseen details.

Vegetable tanning is not merely a superior manufacturing process. It is an ethical position. It is a declaration that time has value, that natural materials possess an intelligence that synthetic chemistry cannot replicate, and that the objects we carry through our lives should be worthy of the lives we carry them through. Chrome tanning serves its purpose in a world that demands volume, speed, and uniformity. But if you are reading this—if you have stayed with me through the chemistry and the philosophy and the economics—you are probably not looking for volume, speed, or uniformity. You are looking for something that lasts. Something that gets better. Something with a soul.

That is what vegetable-tanned leather offers. That is what we build at Marcellino NY. And that is what twenty-five years behind the counter at the Heritage Diner has taught me to recognize in every material, every meal, and every handshake: the unmistakable quality of something made right, by someone who refused to take shortcuts, for someone who knows the difference.

Further Viewing:

- “Chrome Tanned Leather vs. Vegetable Tanned Leather, Explained” — Gentleman’s Gazette: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubRKQQ4QFUE

- “How Is Leather Made?” — Reactions (PBS Digital Studios): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNMpFaYr4eU

Published on The Heritage Diner Blog — heritagediner.com/blog Written from Mount Sinai, New York